If Hernando de Soto and Juan Pardo had been successful and established a series of permanent settlements, we might all be speaking Spanish in this country rather than English. That’s one conclusion that archeologist Rob Beck of the University of Oklahoma likes to tell people about when he describes the discovery of Fort San Juan on the upper Catawba River in Burke County north of Morganton.That fort was established by de Soto’s men in 1567 – a couple of decades before Sir Walter Raleigh’s expedition set out from England and established a colony on Roanoke Island that disappeared – and became known as the Lost Colony.

The Fort San Juan story is told in a new episode of UNC-TV’s “Exploring North Carolina” series produced by narrator Tom Earnhardt of Raleigh and videographer Joe Albea of Greenville. It airs tonight at 8:30 p.m. and repeats Friday, Feb. 1 at 9:30 p.m. and Sunday, Feb. 3 at 6 p.m.The program describes how Beck and other archeologists, including David Moore of Warren Wilson College near Asheville and Christopher Rodning of Tulane, assembled the evidence that linked the 12-acre site in Burke County to a known site at Parris Island. S.C., where Spanish explorers established a fort in what then was called northern Florida.

Continued here:

http://jackbetts.blogspot.com/2008/01/was-first-lost-colony-in-burke-county.html

Thursday, January 31, 2008

De Soto's Fort Located?

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/31/2008 10:10:00 PM

![]()

Labels: burke county, Catawba river, de Soto, Juan Pardo, lost colony, Roanoke island

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

Lost Colony Dig; Probing the Past with Radar

BY ED BECKLEY | SENTINEL CORRESPONDENT

When doctors want to see a body's organs they use an magnetic resonance imaging machine (MRI) to view beautifully clear images of what's inside.

When archaeologists want to see what's below the surface of the earth they are now beginning to use a similar technology called computer-assisted radar tomography (CART).

An archaeologist with the First Colony Foundation was on site at Fort Raleigh Saturday with CART engineers testing the advanced ground penetrating system. Their hope is that CART will prove to be a viable tool to help find artifacts from Sir Walter Raleigh's 16th Century colonies in the future.

The First Colony Foundation comprises a team of top archaeologists who in recent years discovered the expanded Jamestown, Va. settlement. The group also is a partner with the National Park Service in search of the Elizabethan presence on Roanoke Island. It has dug its share of holes along Roanoke Sound the past couple of years.

http://obsentinel.womacknewspapers.com/articles/2008/01/23/top_stories/tops3441.txt

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/29/2008 09:09:00 PM

![]()

Labels: advanced ground penetrating system, CART, fort raleigh, lost colony, radar tomography, Roanoke island

Monday, January 28, 2008

Search for Lost Colony takes a high-tech turn

By Catherine Kozak

The Virginian-Pilot©

January 28, 2008

An innocuous-looking golf course tractor pushing a platform on wheels could help illustrate the nation's oldest mystery.

In the quest for the Lost Colony, the vanished 1587 English settlement on Roanoke Island, archaeologists have conducted numerous explorations in Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, digging and surveying and scanning and scoping.

But they've never used high-tech radar tomography that can produce 3-D images out of data collected from 6 feet, more or less, under ground.

The refined technology, which can also use sound and light waves, gained early fame when inventor Alan Witten used it to help locate fossils from a 120-foot-long dinosaur - called "seismosaur us " - in the late 1980s in New Mexico. The find was fictionalized in Michael Crichton's "Jurassic Park."

"This is fantastic, cutting-edge technology," said Eric Klingelhofer, vice president of the First Colony Foundation, in a telephone interview. "I am eager to see the findings and then compare them with what we know of the archaeology of the site."

On a recent, rainy Saturday morning, Klingelhofer, who is a professor at Mercer University in Georgia, watched as a contractor with Witten Technologies drove the tractor back and forth in the parking lot and grass borders near the ticket booth at Waterside Theatre, where "The Lost Colony" outdoor drama is performed each summer.

"We're picking up the utilities, which is good, because that's what the equipment is designed to do," he said. "But we have picked up some anomalies, which is good."

The veteran archaeologist said the foundation, which has an agreement with the National Park Service to do archaeological investigations at the park, dug on the sound side of the parking lot in 2006. And in the 1990s, archaeologists dug between the earthworks and the theater. The hope, he said, is that Witten's technology, which is costing a couple of thousand dollars, can help pinpoint where significant anomalies, or irregularities, are located before the archaeologists touch a shovel.

http://hamptonroads.com/2008/01/search-lost-colony-takes-hightech-turn

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/28/2008 11:01:00 PM

![]()

Labels: Archaeology, fort raleigh, lost colony, north carolina, radar tomography, roanoke

Sunday, January 27, 2008

Graveyard of the Atlantic

You can stand on Cape Point at Hatteras on a stormy day and watch two oceans come together in an awesome display of savage fury; for there at the Point the northbound Gulf Stream and the cold currents coming down from the Arctic run head-on into each other, tossing their spumy spray a hundred feet or better into the air and dropping sand and shells and sea life at the point of impact.

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/27/2008 09:16:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Atlantic Seaboard, gulf stream, hatteras, north carolina, outer banks, shipwrecks

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Occaneechi Indians

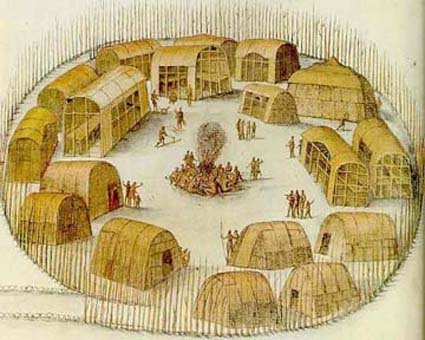

John Lawson, who visited the Occaneechi in 1701, gives us what is probably our latest, best known view of how the Occaneechi were living prior to their incorporation with the Saponi. Coupling Lawson's (Lefler 1967) written account with the information gained by recent excavations at Occaneechi Town by the Research Laboratories of Anthropology (Dickens et al. 1987; Ward and Davis 1988), it is possible to gain a fairly clear picture of a society undergoing rapid change, and yet endeavoring to maintain some semblance of a traditional lifestyle. In a period of time when small fragmented groups across the Piedmont were banding together for mutual assistance and protection, the merging of families and small tribes at Occaneechi Town would not have been unusual.

Occaneechi Town was almost completely abandoned by 1713, when the Occaneechi signed a Treaty of Peace with the Virginia colonial government at Williamsburg. At that point, it is indicated from reading the document that the Occaneechi, Stuckanok, and Tottero, although signing the treaty separately, were dominated by the Saponi. At least, the whites seemed to regard them all as Saponi. Governor Spotswood of Virginia would later refer to the Fort Christanna Indians as all going under the name of Saponi. There are very few references to the Occaneechi as a distinct tribe after the settlement at Fort Christanna, which operated from 1714 to 1717.

After the Indians were settled on the Meherrin River near present-day Lawrenceville, Virginia, a school and minister were provided for their instruction, along with a small company of rangers who were to guard the eastern colonists from attacks by western tribes such as the Cherokee. Once they were "civilized" by the influences of Christianity and the English language, the Saponi were no doubt expected to assist in this duty. The fort also served as a trading center for the Indian trade, but the profits apparently were not great enough to satisfy the project's backers and the fort was closed in 1717.

http://www.ibiblio.org/dig/html/split/report47b.html

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/22/2008 09:01:00 PM

![]()

Monday, January 21, 2008

Roanoke, the Accidental Colony

The Lost Colony, an accident of fate with a tragic outcome that reverberates to this day, should never have happened. The group of colonists sent out by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1587 to establish the Cittee of Raleigh, had never intended to locate on the Island of Roanoke. But after a four month long trip marked by delays, mishaps, evasive tactics and possibly outright sabotage, these some 117 men, women and children were unceremoniously dumped on the island by Captain Fernandez. All but but two of them would vanish without a trace.

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/21/2008 09:46:00 PM

![]()

Sunday, January 20, 2008

THE INDIANS OF PERSON COUNTY NORTH CAROLINA

Newspaper Article - 1948

THE INDIANS OF PERSON COUNTY NORTH CAROLINA

HISTORY OF A PROUD AND HANDSOME TRIBE OF INDIANS NEAR ROXBORO MAY BE CONNECTED WITH LOST COLONY MYSTERY; ABOUT 70 FAMILIES LIVE IN EXTENDED FARMING COMMUNITY

By Tom MacCaughelty

Durham Morning Herald, March 21, 1948

Straddling the North Carolina border in the secluded hills east of U.S. Highway 501 is a community of American Indians whose history has remained as much a mystery as the fate of the Lost Colony. Commonly termed a "mixed-blood" group, these proud people are probably the product of marriages long ago of whites and Indians, and, in fact, have a tradition among themselves which says they are remnants of the Lost Colony. In color they vary between blondes and even red-heads with grey or blue-gray eyes to tawny and sometimes swarthy brunettes with hazel, brown, or black eyes. Some have the straight black hair associated with pure Indian, while others have differing shades of brown hair, either straight or wavy. In general appearance they are well- dressed and clean. They are a handsome people. Their history is mysterious. As Indians, they never have been positively identified. Can they be, as their tradition holds, the long sought descendants of the friendly Indians who received the colonists of John White? Strangely enough, among the approximately 350 people in the scattered farming community, only six family names are represented: Johnson, Martin, Coleman, Epps, Stewart (also spelled Stuart), and Shepherd. Stranger still, three of these names correspond closely with those among the list of Lost Colonists: Johnson, Coleman, and Martyn. But theirs are common English names long familiar in North Carolina, and intermarriage with the proximity to whites would be expected to extend such names among them. (A seventh prominent name among this group is Tally.) As far back as anyone knows, these people have displayed the manners and customs of white settlers, but in this they don't differ from identified Indians.

Unfortunately, as far as settling the question goes, not a single Indian word had been passed down to the present group. If their former manner of speech could somehow be resurrected, there would be a good clue to their identity; for then experts could judge with some degree of accuracy whether they indeed originated among the coastal Algonquin language tribes. If so, there would be a good argument for the Lost Colony theory. If their language were Siouan or some other branch of the inland tongues, the score would be against the Lost Colony tradition.

Dr. Douglas LeTell Rights, author of "The American Indian in North Carolina," (published by Duke University Press in 1947) says that there is a possibility that the people, officially designated as Person County Indians, are descendants of the Saponi, originally a Siouan tribe. He notes that Governor Dobbs reported in 1755 that 14 men and 14 women of the Saponi were in Granville county. Person County was once a part of Granville county. ( Dr. Rights also suggests that these Indians in Person County may be a branch of, or have mixed with, the Indians of Robeson County. The people themselves deny being a branch of the Robeson County Indian, but say that there have been a few marriages between members of the two groups.)

The Person County Indians, if they are of the Saponi, couldn't choose a more highly regarded tribe. (Col. William Byrd, in his History of The Dividing Line describes this tribe.) Whether a remnant of the Lost Colony, or of the proud Saponi, or of some other group, these people have lived in the rolling hills and high plains northeast of Roxboro for countless generations. No one knows how long. According to E. L. Wehrenberg, for 17 years principal of the community school, it was not until 1920 that they were officially recognized by act of the North Carolina legislature as Person County Indians. Before that, however, they had always insisted upon being treated either as Indians or whites. Back in the days of subscription schools, they hired their own white teachers; and under the present county school system have always had white or Indian teachers. Wehrenberg estimates that there are about 70 families in the group. and that about two-thirds of the people live in Person County and the rest across the line in Virginia. This proportion has changed from time to time he says.

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/20/2008 09:27:00 PM

![]()

Labels: byrd, indians, lost colony, north carolina, person county, person indians, robeson county, saponi

Friday, January 18, 2008

Roanoke Island Festival Park attendance up 21 percent

Executive Director Scott Stroh recently announced a 21 percent increase in attendance at Roanoke Island Festival Park for 2007, completing the year with just under 150,000 visitors.

"I am thrilled with our growth and very proud of our staff's tremendous work. Our mission is to involve residents and visitors of all ages in a creative and stimulating exploration of Roanoke Island's historical, cultural, and natural resources and being able to successfully realize this goal with ever increasing numbers of guests is very rewarding for all of us at the Park," said Stroh.

With the commencement of the Exhibit Enhancement Project, 2008 will be another year of growth for the Park. This project includes the creation of an outdoor, interactive American Indian Town and Cultural Educational Center, the re-design of the Park's Visitor Center and placement of site-wide way-finding signage, and the expansion of exhibits in the Roanoke Adventure Museum.

In addition, the State of NC has recently awarded $1 million in improvements to the Outdoor Pavilion. Work will include raising and extending the stage, raising the existing roof, lighting enhancements, updating dressing rooms and restrooms and more. "We are very fortunate to have received significant funds in support of the Park's enhancement and growth. The projects currently underway will dramatically improve the guest experience at the Park and better enable us to meet important needs in our community," said Stroh.

Roanoke Island Festival Park is an interactive family attraction that celebrates the first English settlement in America. The centerpiece of the 25-acre island park is Elizabeth II, a representation of one of seven English ships from the Roanoke Voyage of 1585.

Full Article Here:

http://obsentinel.womacknewspapers.com/articles/2008/01/16/business/bus354.txt

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/18/2008 10:08:00 AM

![]()

Labels: lost colony, north carolina, roanoke

Thursday, January 17, 2008

Virginia Indian Tribes

Part 2

Pamunkey Tribe

The Pamunkey tribe was one of the largest in the Powhatan paramount chiefdom . The tribe is now based in King William County on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation on the banks of the Pamunkey River. This 1,200-acre reservation is part of land awarded to the Pamunkey in the 17th century. The reservation lands were confirmed as part of the Articles of Peace, a 1677 treaty with the King of England which remains the most important existing document describing Virginia’s historic stance regarding Indian lands. Research on the reservation indicates evidence of Native occupation going back 10,000 – 12,000 years. Pamunkey tribal members continue the traditions of pottery making, fishing, hunting, and trapping. Like the Mattaponi, the Pamunkey place an emphasis on the importance of the shad in the river adjacent to their reservation, and they maintain a shad hatchery to ensure the continuation of the healthy shad runs in the Pamunkey River.

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/17/2008 05:26:00 PM

![]()

Labels: indians, Mattaponi, Pamunkey, virginia dare

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

Virginia Indian Tribes

Part 1

The Chickahominy Indian Tribe, whose name has been translated as “course ground corn people,” was officially recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia General Assembly on March 25, 1983. With approximately 875 Chickahominy people living in the vicinity of the Tribal Center, the Chickahominy are based in Charles City County near the many towns along the Chickahominy River where the tribe lived in 1600. The Chickahominy had early contact with the English settlers because of their proximity to Jamestown, and they taught early colonists how to survive by growing and preserving their own food. As the English prospered and claimed more land, the Chickahominy tribe was forced out of their homeland. The treaty of 1646 awarded reservation land to the Chickahominy and other tribes in the “Pamunkey Neck” area of Virginia where the Mattaponi reservation exists todays. After 1718, they were forced off this reservation, and over the ensuing years Chickahominy families moved to Chickahominy Ridge in present day Charles City County where they now reside. Here the tribe purchased land and established the Samaria Baptist Church, which remains an important focal point for the community.

The Chickahominy Indian Eastern Division (CIED) also originated with the historic Chickahominy tribe. This tribe, based in New Kent County, was established in the early 20th century and has approximately 130 members today. Their members established the Tsena Commocko Baptist Church, and in recent years have purchased approximately 40 acres as tribally held land.

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/16/2008 10:16:00 PM

![]()

Labels: Chickahominy, indian, virginia

Sunday, January 13, 2008

Roanoke Colonies

The Roanoke Colony on Roanoke Island in Dare County in present-day North Carolina was an enterprise financed and organized by Sir Walter Raleigh in the late 16th century to establish a permanent English settlement in the Virginia Colony. Between 1585 and 1587, groups of colonists were left to make the attempt, all of which either abandoned the colony or disappeared. The final group disappeared after a period of three years elapsed without supplies from England, leading to the continuing mystery known as "The Lost Colony." The principal hypothesis is that the colonists disappeared and were absorbed by one of the local indigenous populations, although the colonists may possibly have been massacred by the Spanish. Other theories include a massacre by some of the hostile local tribes.

Sir Walter Raleigh had received a charter for the colonization of the area of North America known as Virginia from Queen Elizabeth I of England. The charter specified that Raleigh had ten years in which to establish a settlement in North America or lose his right to colonization.

Sir Walter Raleigh had received a charter for the colonization of the area of North America known as Virginia from Queen Elizabeth I of England. The charter specified that Raleigh had ten years in which to establish a settlement in North America or lose his right to colonization.

Raleigh and Elizabeth intended that the venture should provide riches from the New World, and a base from which to send privateers on raids against the treasure fleets of Spain.

In 1584, Raleigh dispatched an expedition to explore the eastern coast of North America for an appropriate location. The expedition was led by Phillip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, who chose the Outer Banks of modern North Carolina as an ideal location from which to raid the Spanish, who had settlements to the South, and proceeded to make contact with local American Indians, the Croatan tribe of the Carolina Algonquians.First Group

The following spring, a colonizing expedition composed solely of men, many of them veteran soldiers who had fought to establish English rule in Ireland, was sent to establish the colony. The leader of the settlement effort, Sir Richard Grenville, was assigned to further explore the area, establish the colony, and return to England with news of the venture's success. The establishment of the colony was initially postponed, perhaps because most of the colony's food stores were ruined when the lead ship struck a shoal upon arrival at the Outer Banks. After the initial exploration of the mainland coast and the native settlements located there, the natives in the village of Aquascogoc were blamed for stealing a silver cup. In response the last village visited was sacked and burned, and its weroance (tribal chief) executed by burning.

Despite this incident and a lack of food, Grenville decided to leave Ralph Lane and approximately 75 men to establish the English colony at the north end of Roanoke Island, promising to return in April 1586 with more men and fresh supplies.

By April 1586, relations with a neighboring tribe had degraded to such a degree that they attacked an expedition led by Lane to explore the Roanoke River and the possibility of the Fountain of Youth. In response he attacked the natives in their capital, where he killed their weroance, Wingina.

As April passed there was no sign of Grenville's relief fleet. The colony was still in existence in June when Sir Francis Drake paused on his way home from a successful raid in the Caribbean, and offered to take the colonists back to England, an offer they accepted. The relief fleet arrived shortly after the departure of Drake's fleet with the colonists. Finding the colony abandoned, Grenville decided to return to England with the bulk of his force, leaving behind a small detachment both to maintain an English presence and to protect Raleigh's claim to Virginia.

Second group

In 1587, Raleigh dispatched another group of colonists. These 121 colonists were led by John White, an artist and friend of Raleigh's who had accompanied the previous expeditions to Roanoke. The new colonists were tasked with picking up the fifteen men left at Roanoke and settling farther north, in the Chesapeake Bay area; however, no trace of them was found, other than the bones of a single man. The one local tribe still friendly towards the English, the Croatans on present-day Hatteras Island, reported that the men had been attacked, but that nine had survived and sailed up the coast in their boat.

The settlers landed on Roanoke Island on July 22 1587. On August 18, White's daughter delivered the first English child born in the Americas: Virginia Dare. Before her birth, White reestablished relations with the neighboring Croatans and tried to reestablish relations with the tribes that Ralph Lane had attacked a year previously. The aggrieved tribes refused to meet with the new colonists. Shortly thereafter, George Howe was killed by natives while searching for crabs alone in Albemarle Sound. Knowing what had happened during Ralph Lane's tenure in the area and fearing for their lives, the colonists convinced Governor White to return to England to explain the colony's situation and ask for help. There were approximately 116 colonists—115 men and women who made the trans-Atlantic passage and a newborn baby, Virginia Dare, when White returned to England.

Crossing the Atlantic as late in the year as White did was a considerable risk, as evidenced by the claim of pilot Simon Fernandez that their vessel barely made it back to England. Plans for a relief fleet were initially delayed by the captains' refusal to sail back during the winter. Then, the coming of the Spanish Armada led to every able ship in England being commandeered to fight, which left White with no seaworthy vessels with which to return to Roanoke. He did manage, however, to hire two smaller vessels deemed unnecessary for the Armada defense and set out for Roanoke in the spring of 1588. This time, White's attempt to return to Roanoke was foiled by human nature and circumstance; the two vessels were small, and their captains greedy. They attempted to capture several vessels on the outward-bound voyage to improve the profitability of their venture, until they were captured themselves and their cargo taken. With nothing left to deliver to the colonists, the ships returned to England.

Because of the continuing war with Spain, White was not able to raise another resupply attempt for two more years. He finally gained passage on a privateering expedition that agreed to stop off at Roanoke on the way back from the Caribbean. White landed on August 18, 1590, on his granddaughter's third birthday, but found the settlement deserted. He organized a search, but his men could not find any trace of the colonists. Some ninety men, seventeen women, and eleven children had disappeared; there was no sign of a struggle or battle of any kind. The only clue was the word "Croatoan" carved into a post of the fort and "Cro" carved into a nearby tree. In addition, there were two skeletons buried. All the houses and fortifications were dismantled. Before the colony disappeared, White established that if anything happened to them they would carve a maltese cross on a tree near their location indicating that their disappearance could have been forced. White took this to mean that they had moved to Croatoan Island, but he was unable to conduct a search; a massive storm was brewing and his men refused to go any further. The next day, White stood on the deck of his ship and watched, helplessly, as they left Roanoke Island.

Full Article Here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roanoke_Colony

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/13/2008 11:30:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Croatoans, grenville, indian, lost colony, queen elizabeth, roanoke, sir walter raleigh

Wednesday, January 9, 2008

HATTERAS DIG IN 1997 UNEARTHED IMPORTANT FINDS

Sunday, June 15, 1997

After unearthing artifacts from two living room-sized sand pits, archaeologist David S. Phelps may well be on the trail of the famed ``Lost Colony'' of Roanoke Island.

Phelps, director of East Carolina University's Coastal Archaeology Office, has been digging on North Carolina's Outer Banks for more than a decade. This spring his team uncovered objects that could indicate that at least a few of the first English settlers in America who mysteriously disappeared from Sir Walter Raleigh's colony migrated south onto Hatteras Island.

Colonists who left the Fort Raleigh area between 1587 and 1590 may have mingled with the Croatan Indians, whose capital was the present town of Buxton - now the home of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

``The Native Americans of this area were at least trading artifacts with the English - if not living with some of the Lost Colonists,'' Phelps said Thursday from alongside one of the 8-foot-deep dig sites. ``We found much more than we'd hoped to here. This is certainly part of the Lost Colony story.''

Handmade lead bullets, pieces of white and red clay pipes, a leather clasp, fragments of European pottery and even a nickle-sized corroded brass or copper coin with a tiny hole drilled in each end are among Phelps' favorite finds from the recent dig. The coin, he said, is similar to a 1563 coin found on Roanoke Island, about 50 miles to the north.

His team also discovered two fire hearths where Phelps said American Indians and colonists may have manufactured weapons and tools together.

Bill Kelso, who directs Jamestown's Rediscovery archaeological project near Williamsburg, Va., said he is ``very excited'' about Phelps' finds.

``It is entirely possible that some of the Lost Colonists went in that direction, toward Hatteras,'' Kelso said Friday. ``That may have been why they left that word `CROATOAN' carved in the tree. We really have no information about European artifacts found in America that date to the 16th century.

``I'd really love to see what Dr. Phelps has found.''

The ``Lost Colony'' legacy began in 1584 when Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe first explored North America for England's Queen Elizabeth. Outer Banks History Center curator Wynne Dough said there is ``considerable controversy over where Amadas and Barlowe first set foot on land. Some say it was between Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout.''

Those men never set up camp in America. But the next year, Englishman Ralph Lane led an expedition back to the Outer Banks to establish an encampment on Roanoke Island. Capt. John White organized Raleigh's colony of 117 men, women and children the following year - in 1587.

Colonists were supposed to establish a permanent settlement on Roanoke Island. White returned to England for supplies later that year. But war broke out in Europe and he didn't return to America until 1590.

By then, all of the colonists had disappeared.

Full Article Here:

SORRY THIS LINK NO LONGER WORKS AS IT DID WHEN I FIRST WROTE THIS ARTICLE

http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/VA-news/VA-Pilot/issues/1997/vp970615/06160222.htm

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/09/2008 10:25:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Archaeology, Arthur Barlowe, artifacts, Croatoans, hatteras, indians, john white, kelso, lost colony, outer banks, Philip Amadas, roanoke, signet ring

Monday, January 7, 2008

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

This is a book to challenge preconceived ideas about the Native Indigenous Peoples of North and South America. And a must read for anyone interested in the History of these people. Janet Crain

1491 is not so much the story of a year, as of what that year stands for: the long-debated (and often-dismissed) question of what human civilization in the Americas was like before the Europeans crashed the party. The history books most Americans were (and still are) raised on describe the continents before Columbus as a vast, underused territory, sparsely populated by primitives whose cultures would inevitably bow before the advanced technologies of the Europeans. For decades, though, among the archaeologists, anthropologists, paleolinguists, and others whose discoveries Charles C. Mann brings together in 1491, different stories have been emerging. Among the revelations: the first Americans may not have come over the Bering land bridge around 12,000 B.C. but by boat along the Pacific coast 10 or even 20 thousand years earlier; the Americas were a far more urban, more populated, and more technologically advanced region than generally assumed; and the Indians, rather than living in static harmony with nature, radically engineered the landscape across the continents, to the point that even "timeless" natural features like the Amazon rainforest can be seen as products of human intervention.

Time Line Here:

http://www.amazon.com/1491-Revelations-Americas-Before-Columbus/dp/140004006X

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/07/2008 09:55:00 PM

![]()

Labels: amazon rainforest, bering land bridge, charles c. mann, columbus, indians, south america

Tuesday, January 1, 2008

Historic Edenton, North Carolina

Historic Edenton, North Carolina

So here in this region was established the first permanent settlement in North Carolina, the "mothertown" of the State. Edenton at once became the focal point of civilization in the Province, the capital of the Colony and the home of the Royal Governors. Supposedly incorporated in 1715 as "The Towne on Queen Anne's Creek," and running through a subsequent diversity of titles such as "Ye Towne on Mattercommack Creek" and "The Port of Roanoke," in 1722 the spot was named Edenton in honor of Governor Charles Eden.

"Here," wrote an early historian, "was a colony from civilized life, scattered among the forests, resting on the bosom of nature, with absolute freedom of conscience and where benevolent reason was the simple rule of its conduct."

And here, wrote Lawson in 1708, "the fame of this new discovered summer country spread through the other colonies and in a few years drew a considerable number of families thereto, who all found land enough, and that which was very good and commodiously seated both for profit and pleasure."

"The women have brisk and charming eyes," commented Lawson further descriptively of the small primal population, "which sets them off to good advantage. They marry very young, some at 13 or 14, and she that stays 'til 20 is reckoned a very indifferent character; as for the men they are commonly of a bashful, sober behavior but are kind and hospitable to all that come to visit them."

The records are clear that as the first settlers grounded their rude craft on the shores of the beautiful Albemarle Bay upon which Edenton is situated, an almost impenetrable wilderness confronted them and defied their early attempts at colonization, but with steadfast perseverance and determination they wrested from nature and the Red Men a foothold from which North Carolina has sprung and built itself a place in the commonwealth of states

Across the little settlement, as at the pioneer colony on Roanoke Island, was thrown a high timbered and palisaded fence with entrance gates defended by a rude fort. At night, perhaps, eagle-eyed riflemen kept constant watch for Indians, and the repeated cry "All's Well" fell as a soothing benediction upon the ears of the brave villagers, exhausted no doubt from the day's labor of erecting homes and clearing woodlands. Frequent attacks were made by the Indians, but soon after 1712 a treaty of peace, still preserved in its original form on parchment, was made whereby the Aborigines withdrew to other lands. A phrase from this treaty sets forth "That there be firm, perpetual and inviolable peace to continue as long as the sun and moon endure between all and every the inhabitants and people of North Carolina and all the nation and people of the Tuscaroroe Indians-- that there be always a friendly and amicable correspondence between the said English and Tuscaroroe Indians."

From the very nature of the struggles and hardships endured by this little community it was but natural that a passionate love of freedom and liberty should have taken deep root here, and history confirms the fact that resistance to British authority existed here one hundred years before the Revolution, and that the frequent rebellions and early disturbances in this section were nothing less than resistance to illegal and usurped power, and evidenced a contest for political and religious independence. These were but long shadows cast before the Mighty Revolution and permits this little colony to be styled one of the first birthplaces of that epochal struggle.

From its very beginning to the time when freedom from England was finally achieved Edenton was a hot-bed and center of continuous revolt and resistance to the Crown. Unjust, oppressive taxes, land rents, cruel and unusual punishments for crime, kept the community in constant turmoil, and the records of these stirring times reflect the grim determination of the people to throw off the domination of the British and gain for themselves that new freedom for which they had braved the many hardships and dangers incident to the settlement of this new land. Countless are the references in the Colonial Records of North Carolina as to the truth of these assertions, and the small town warfares and oppositions on the streets of Edenton and about its "Publick Parade," as its present day Commons was originally called, are reported with freedom and much candor.

These disputes, actually the growing pains of a people trying to be free, kept the jail overcrowded, the stocks, the rack, the pillory and the ducking stool, well overworked. Such smoulderings of discontent and discord broke into vivid flame on August 22, 1774, when a mass meeting of citizens, presided over by the fiery Daniel Earle, rector of St. Paul's Church, gathered at the court house, publicly denounced the unjust imposition of taxes and prosecutions and condemned the Boston Port Act, openly declaring that "the cause of Boston was the cause of us all." Quickly followed on October 25 of the same year the famous Edenton Tea Party, particularized elsewhere, when 51 ladies of the town met and openly resolved that "We, the Ladys of Edenton, do hereby solemnly engage not to conform to the Pernicious Custom of Drinking Tea," or that "We, the aforesaid Ladys will not promote ye wear of any manufacturer from England until such time that all acts which tend to enslave our Native country shall be repealed."

And in furtherance of this attitude of protest and a month or more prior to the Continental Congress's Declaration of Independence, the Vestry of St. Paul's Church, in a written document called "The Test," added an ecclesiastical note of protest in this wise--"We, the subscribers, professing our allegiance to the King and acknowledging the constitutional executive power of Government, do solemnly profess, testify and declare that we do absolutely believe that neither the Parliament of Great Britain nor any member of a constituent branch thereof, have a right to impose taxes upon these colonies to regulate the internal policy thereof; that all attempts by fraud or force to establish and exercise such claims and powers are violations of the peace and security of the people and ought to be resisted to the utmost, and that the people of this Province, singly and collectively, are bound by the Acts and Resolutions of the Continental and Provincial Congresses, because in both they are freely represented by persons chosen by themselves. And we do solemnly and sincerely promise and engage under the sanction of Virtue, Honor and the Sacred Love of Liberty and our Country, to maintain and support all and every the Acts, Resolutions and Regulations of the said Contintental and Provincial Congresses to the utmost of our power and ability."

Then came the Revolution and Edenton was ready through the leadership of her illustrious sons of that period to take her stand at the forefront among the towns of the entire nation to add her services in the cause of freedom. "Within the vicinity of Edenton," says a writer, "there was in proportion to its population a greater number of men eminent for ability, virtue and erudition than in any other part of America." Another writer said: "there are but few places in America which possess so much female artillery as Edenton," referring, of course, to the action of the ladies of the Tea Party. The military leaders numbered General Edward Vail, Colonel Thomas Benbury and Colonel James Blount and many others, who raised company after company and marched off to aid Washington.

Joseph Hewes, a Signer of the Declaration of Independence, was a citizen of Edenton, a large ship-owner and merchant, who carried on a great trade with England and the West Indies. War meant a tremendous financial sacrifice to Hewes but, true patriot that he was, he signed the Declaration and put his entire fleet at the disposal of the Continental forces. To Hewes the Nation is indebted for the brilliant services of John Paul Jones. Hewes who was Secretary of the Naval Affairs Committee of the Continental Congress and virtually the first Secretary of the Navy, was directly responsible for the elevation of Jones to his position in the new Navy. Jones never forgot his patron and sponsor and many letters are extant telling of the great gratitude he felt for Hewes' interest in him. "You are the Angel of my happiness; since to your friendship I owe my present enjoyments, as well as my future prospects. You more than any other person have labored to place the instruments of success in my hands." Hugh Williamson, celebrated physician, was another worthy son of Edenton during the Revolution. Dr. Williamson, at his own expense, fitted out ships with supplies for the American Army, was Surgeon-General of the State Colonial troops and rounded out a brilliant career by signing the Constitution of the United States in 1787.

Samuel Johnston of Edenton was another nationally known patriot during these stirring times. He was a leader in the movement for freedom and was the first United States Senator from North Carolina. James Iredell, brother-in-law of Governor Johnston, was the political leader of this community for many years. After distinguished services to his country otherwise he was appointed by George Washington to the Supreme Court of the United States. His opinions were famous in the field of jurisprudence and he was considered one of the outstanding jurists of his time.

During its long history of nearly three centuries Edenton naturally has passed through many vicissitudes of fortune. Fires, storms and other calamities have taken their toll during the years but probably no one occurrence threw such an apprehension of certain doom into its inhabitants as on a morning of April, 1781, when 80-year-old Jeremiah Mixson, the town crier, shrilled the clarion news to the inhabitants that Cornwallis was sending forces south from Suffolk to burn Edenton in revenge for the part Edenton had played in fomenting the resistance to British authority. Panic ensued. People ran to and fro not knowing what to do. Alarms were sounded, bells of the town were rung and everyone congregated on the Green seeking some way to escape the impending peril. Resistance was out of the question as practically the entire male population was away in Washington's army. Soon a messenger arrived by boat from Windsor, where Edenton's danger from British attack had become known. He offered the people of Edenton refuge in his Bertie County town. The proffer was accepted eagerly and thankfully and by dawn Edenton was deserted. No living human or animal was left in town. For seven days the community was like a city of the dead. Then came better news. Cornwallis, hard pressed, was having his own troubles. His Suffolk forces were recalled, the intended invasion fell flat, and the people of Edenton returned rejoicingly to their homes and carried on.

Then came the Civil War, with its attendant suffering and reconstruction. Edenton as had been its custom for over two hundred years, patriotically threw itself into the fray and sent several units to fight for the southern cause. Among these was its famous Edenton Bell Battery, whose field pieces, as in countless other sections of the south, were cast from the town bells in response to a general call to do so sent throughout the Confederacy and which was immortalized in a war Iyric by F. Y. Rockett. The Edenton Bell Battery was organized in 1862 by Captain William Badham and was engaged in many battles throughout the war, finally surrendering to Sherman in 1865.

Although now a modern city, Edenton is fortunate in having preserved many old buildings rich in their association with Colonial times, and the visitor finds here today numerous spots of historic interest carefully kept in their original setting.

Among the priceless buildings here is the Court House, erected in 1767. The oldest Court House in North Carolina, and is an architectural gem of national reputation. A sketch of its life reads like a panoramic review of the life of North Carolina: the hardships of the early colony, the struggles of revolution, civil war and reconstruction; all finally unfolding into the commonwealth that is the Old North State of today. Through six conflicts the call to arms has resounded within its walls; it can recall the inauguration of every President of the United States; Governors from the time of Josiah Martin have spoken from its rostrum; Princes and Presidents have danced on its floors and the most illustrious lawyers of the State have pleaded their causes before its bar.

On the second floor is the famous panelled room, long used in the old days as a town social center. Also on the second floor is the lodge-room of the Masons, containing among other priceless relics, the chair used by George Washington in the lodge at Alexandria, Virginia.

The oldest corporation in North Carolina, St. Paul's Parish, was formed in 1701 and immediately erected a small wooden chapel on the shores of the sound on "Hayes" plantation. This was the first church in the State. We have it on the authority of the Rev. Mr. Rainsford, one of the early ministers, that this first edifice proved inadequate to accommodate the large congregations attending his sermons and he wrote that on many occasions he was compelled to hold his meetings out in the open, under the trees. Consequently, a second building was constructed, and the third, the present magnificent pile, St. Paul's, was begun in 1736. It is known as the "Westminster Abbey" of North Carolina, and beneath its ancient oaks sleep scores of the founders of our commonwealth.

"Bandon," situated on the Chowan River, 15 miles above Edenton, was the former home of Rev. Daniel Earle, who established there the first classical school for boys in North Carolina, the initial school having been founded at a spot called Sarum, near the Gates County line. Daniel Earle, affectionately called "Parson" Earle was rector of St. Paul's, Edenton, during the Revolutionary period and a fiery patriot.

The "Cupola House", built in 1758 by Francis Corbin, land agent of Lord Granville in Carolina, now houses the Edenton Museum and the Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library.

The outstanding colonial home of the entire State of North Carolina is the magnificent seat of Governor Samuel Johnston. Situated in the midst of its one thousand fertile acres and overlooking Edenton Bay, "Hayes", a pure American type, is a treasure-house of early Americana. Priceless portraits adorn its walls and its library of thousands of old volumes and manuscripts contains many rare "first editions."

"Beverly Hall", the old State Bank from 1811 to 1836, is now used as a residence. Its huge secret vault, encased in steel, and its key, weighing two pounds, are reminders of the cumbersome banking equipment of an older day.

Eastward from Hayes and stretching along the North Shore of Albemarle Sound lie other fine old estates and homes, including "Montpelier", "Atholl", "Mulberry Hill", "Greenfield", and others.

Many other objects and places of interest attest Edenton's association with the making of the Commonwealth. Some of these are the Revolutionary cannon brought from France and now mounted on Edenton's "Battery" at the foot of the Courthouse Green; the site of the famous Edenton Tea Party, marked by a Colonial teapot mounted on a Revolutionary cannon; the homes of Judge Iredell, Governor Iredell, the Littlejohn house and the Civil War fort at "Wingfield" on the Chowan River.

And such is and was the new-old Edenton: proud of her past and progressive for the future; democratic, yet dignified; pressing forward for a newer, better life, yet mindful of the experiences of the years; and ever clinging to all ancient things that are of good report, she moves to her destiny of a newer day.

Edenton, North Carolina. In This Booklet Edenton Invites Your Atention to its Historical Attractions and its Advantages for Industry and Agriculture. Edenton, NC: The Chowan Herald Print, 1937.

* Some say Edenton, NC was the second English Colony, an honor that usually goes to Jamestown. Could these "English" have been the "Blue Eyed Indians", mixed blood descendants of the Lost Colonists?Reader comments welcome.

For those of you who knew Edenton existed, did you know the original residents were the Algonquian speaking Chowanac and Weapemeoc (don't ask me to pronounce that) Indians? That it was the first permanent European colony settled (not counting the lost colony of Roanoke)? That it was the first colonial capital of North Carolina? That famous residents include signers of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution? That it was first called "The Towne of Queen Anne's Creek"? We didn't until we watched a 15-minute video at the Visitors Center where we loaded up on brochures.

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

1/01/2008 08:21:00 PM

![]()

Labels: Albemarle, Chowanac, Cornwallis, Edenton, indians, john lawson, Lord Granville, north carolina, roanoke, Tuscarora, Weapemeoc