CHAPTER 1. “A Very Large Nation”

by Steven Pony Hill, Copyright ©2005 all rights reserved.

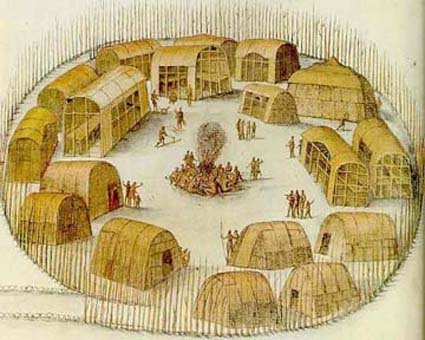

Little is known about the Cheraw Tribe prior to their first encounters with Europeans in 1534. They were known to the Cherokee as “Ani-Suwa’li”, or “the Suwali people.” The Cheraw Tribe was actually a loose confederation of tribes who all spoke a version of the Siouan language. Known by such general names as the Cheroenhaka, Esaw, Isaw, Sara, and Saraw, this confederacy of eastern Siouan peoples included the Manahoac, Hassinunga, Shakori, Eno, Meherrin, Nahyssan, Nottaway, Occaneechi, Saponi, and Tutelo. Encountering them in 1701, explorer John Lawson described them as “the Esaw Indians, a very large Nation, containing many thousands of people.”

In the early 1600’s many important historic incidents occurred which would affect the Cheraw descendents for generations. Already suffering from constant raids from the Iroquois on their northern border, the Tuscarora to the south, and the Cherokee west, the Cheraw now faced a new threat, European colonists pushing inland from the east. Cheraw Indians being taken captive by raiding parties of Iroquois and Cherokee were being sold as slaves to the colonists and this did nothing to better the situation. From 1616 to 1630, Opechancanough, successor of Powhatan, and chief over all the Algonquin speaking tidewater tribes, expressed his displeasure with the encroaching white men by waging a bloody war. Indian captives were taken in increasing numbers from the tidewater tribes during this time and forced into slavery. Those Indians not taken as slaves were forced to wander the Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina area.

In 1657 the English forced most of the Powhatan remnants onto reservations in Virginia and the Siouan tribes were gathered in four main concentrations:

“The Monacan, along the James; the Saponi along the Rivana and James

Rivers and Otter Creek; the Tutelo in the Roanoke Valley; and the

Occaneechi on islands at the confluence of the Roanoke> and Dan Rivers.”

Arguably the most influential event to occur in the 1600’s happened in 1660 when Virginia determined that “…an Indian sold by another Indian or an Indian who speaks English and who desires baptism will now receive his or her freedom.” This allowed many Algonquin and Siouan war captives held in slavery in the colonies to regain their freedom, but it also provided incentive for their masters to downplay the Indian ancestry of those in servitude in order to retain them. These former slaves quickly rejoined their tribesmen bringing with them their acquired skills as carpenters, wheelwrights, and ferry operators. Most importantly, these newly freed Indians brought with them their new English names and Christian religion. Unfortunately they also retained the stigma of being former slaves, a condition which would cause their white neighbors to eye them with suspicion for generations.

In 1713, the confederated eastern Siouan Nations signed a Treaty of Peace with the Virginia Colonial government at Williamsburg. Among the different Nations represented were the Occaneechi, the Stuckanok, the Tottero, and the Saponi. At the invitation of Governor Spottswood of Virginia, these Indians settled a four-square-mile reservation encompassing the north and south side of the Meherrin River. On the north banks were the Nansemond and related Algonquin-speaking bands, on the south were the Siouan-speaking Tutelo, Saponi, Cheroenhaka, Eno, and also an Iroquoian-speaking band of Tuscarora who had survived the war with the Carolina settlers just 2 years earlier. Spottswood endorsed the construction of Fort Christanna where the Indian children had mandatory training in academics and Christianity. After the closing of the Fort Christanna school a few of the students followed headmaster Charles Griffin and enrolled at the Brafferton Indian School at William and Mary.

Because of the continued hostilities between these Nations and the Iroquois to the north, the governors of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia held a conference at Albany in September of 1722 to hammer out a peaceable agreement between the Tribes on their borders. Governor Spottswood undertook negotiations for the “Christanna Indians” who were composed of “the Saponies, Ochineeches, Stenkenoaks, Meipontskys, and Toteroes.”

In addition to their traditional native enemies, it is obvious that the remnant tribes considered the encroaching white settlements as an almost equal threat. It also appears that, on the subject of trespassing whites, even the Algonquin and Siouan peoples could agree and cooperate. On October 24, 1723 the Virginia Government spoke out on behalf of the Meherrin and Nansemond Nations and warned the North Carolinians:

“Whereas, the Maherin and Nansemond Indians have this day complained

that notwithstanding the repeated orders of this government for security to them the possession of their lands, whereon they have many years past been seated, between the Nottoway and Maherine Rivers, divers persons under pretense of grants form the Government of North Carolina surveyed the lands of the said Indians and begun to make settlements within their cleared grounds.”

This report is especially interesting as it implies that portions of the Nansemond had obviously moved west of their ancestral homes around Norfolk, Virginia, and were living with the Meherrin between the Nottoway and Meherrin Rivers.