Throughout this period the Bear River and Machapunga Indians continued their petty annoyances, and the settlers continued to petition the government for something to be done about the situation. Little seems to have been though for the settlers remained prey to roving bands of Indians who would enter a settler's home, ransack it, kill his hogs, and assault him if he protested.

Wednesday, April 23, 2008

The Tuscarora War, 1711-1715

— The Tuscarora War, 1711-1715 —

Bath State Historic Site

The Indians Retaliate . . .

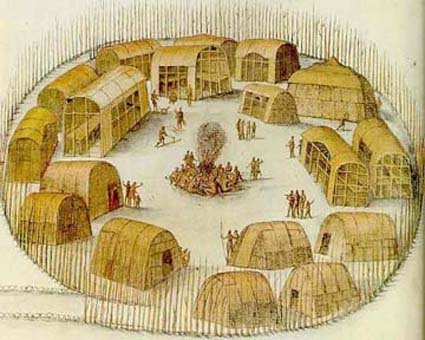

From the first, there had been an Indian problem in Bath County. While disease had broken the power of the Pampticough tribe in the neighborhood of Bath, there remained many other small tribes scattered throughout Bath County. Behind these small tribes lay the powerful Tuscarora, an Iroquoian tribe closely connected to the Five Nations in New York. The movement of settlers into Bath County and up the Pamlico and Neuse Rivers had been watched with fear and resentment by the Tuscarora and the smaller tribes in this area. Favorite hunting grounds were being overrun and choice village sites were becoming sites for the settlers' towns.

While the chief danger to the settlers from Indian attacks came from the many Tuscarora, the first resistance the land-hungry settlers of Bath County faced came from the smaller tribes into whose territory they first moved. The first to resist the advancing tide of civilization were the Core (sometimes called Coree) and Nynee Indians, who lived south of the Neuse River. In 1703 they were declared public enemies by the Carolina government, which was determined to carry on a war against them. While the records of this conflict are gone, the Indians evidently were defeated, for the next time they are mentioned in history, they have moved into the interior where the Tuscarora have granted them land only six miles from one of their chief towns.

Throughout Bath County during the first decade of the eighteenth century, rumors of Indian plots and conspiracies constantly spread. In 1703, Lionel Reading wrote that an Indian had told one settler that several villages had "fully resolved to make trail (trial) of it for to see which is the ardiest." The next year word spread that some of the Tuscarora towns near the Pamlico settlement were becoming unusually friendly with the Bear River Indians, with the apparent intention of inciting them to attack the whites. About this same time the Machapunga Indians began to harass the settlers, which took the form of threats, hog-stealing, and actual assault on one settler. The settler did not fail to note that the Machapunga moved their village "nigh a wildnernesse where upon the least Intimation they can easily repair without being pursued."

Throughout this period the Bear River and Machapunga Indians continued their petty annoyances, and the settlers continued to petition the government for something to be done about the situation. Little seems to have been though for the settlers remained prey to roving bands of Indians who would enter a settler's home, ransack it, kill his hogs, and assault him if he protested.

Throughout this period the Bear River and Machapunga Indians continued their petty annoyances, and the settlers continued to petition the government for something to be done about the situation. Little seems to have been though for the settlers remained prey to roving bands of Indians who would enter a settler's home, ransack it, kill his hogs, and assault him if he protested.

In 1707, Robert Kingham reported that the settlers on the Pamlico told him that "they expected ye Indians every day to come and cutt their throat and yet they had no person to head ym [them] or Else they would goe and secure all ye Pamticough Indians."

Obviously, relations between the early white settlers and the Indians were not as harmonious as many historians have pictured. From the first, the Indians resented the colonists' encroachment upon their territory and used every means they had to show this resentment, at times resorting to out and out war. The Tuscarora, by all odds the dominant Indian power in North Carolina, had watched the steadily growing settlements with distrust, seething over each movement into a new area. When the tide of civilization flowed into the Pamlico-Neuse region, they saw the handwriting on the wall. They now decided they must make a stand or gradually be overrun, and by the summer of 1711, apparently decided to try to destroy the whites.

Other actions by the whites also caused the Indians to act. Perhaps nothing made them hate the settlers of Bath County more than the whites' kidnapping and enslavement of their people. By 1710, this had reached such proportion that the Tuscarora sought permission of the government of Pennsylvania to settle in that colony so that their children born and those soon to be born might have room to sport and play without danger of slavery. In their quaint phrases, they begged "a cessation from murdering and taking them, that by the allowance thereof, they may not be afraid of a moose, or any other thing that Ruffles the Leaves."

Closely akin to this problem was the ill-feeling and misunderstanding surrounding trade between Indians and the white settlers. The whites felt that the Indian traders were hard men who drove hard bargains. Conversely, the Indians soon saw that the whites were cheating them in their transactions, for the traders, John Lawson tells us, esteemed it "a Gift of Christianity not to sell to them so cheap as [they did] to the Christians." The traders, knowing the Indians' weakness for strong drink, often got the Indians drunk as a means of defrauding and stripping them of their property. One observer reports that the Indians were never "contented with a little, but when once begun, they must make themselves quite drunk; otherwise they will never rest, but sell all they have in the World, rather than not have their full dose."

Certainly another reason for the Indians' decision to take up the tomahawk was the indignities inflicted on them by the white settlers. The Indians were a proud, dignified, and lordly people, unaccustomed to the condescending and often insulting way the whites often treated them. Just a few days before they sought their revenge they complained to a settler who had been unfortunate enough to fall into their hands, that they "had been very badly treated and detained by the inhabitants of the Pamtego, Neuse and Trent Rivers, a thing which was not to be longer endured." That the whites, who looked upon the Indians "with Scorn and Disdain" and considered them "little better than Beasts in Human Shape," eventually felt their wrath cannot be too surprising.

Full Article Here:

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

4/23/2008 09:16:00 PM

![]()

Labels: bath county, john lawson, neuse river, north carolina indians, Pamlico, Tuscarora, tuscarora war