Marjorie Hudson, Among the Tuscarora: The Strange and Mysterious Death of John Lawson, Gentleman, Explorer, and Writer, North Carolina Literary Review, 1992

Text and Image(s) from Journal Article

[page 62]

AMONG THE TUSCARORA

THE Strange AND Mysterious Death Of

John Lawson

GENTLEMAN, EXPLORER, AND WRITER

[Image from the North Carolina State Archives, Division of Archives and History]

The death of John Lawson, a drawing by Baron Cristoph Von Graffenried

by Marjorie Hudson

They've taken his clothes, picked the straight razor out of his pocket: one brave fingers it, touches the blade - bright blood springs from his thumb and he laughs. The pitch pine split by the women is ready, a clay pot full of splinters, and now, one by one, the women thread these needles into his flesh, pushing just hard enough to bring the blood, to press past the strange white skin to the devil underneath. The man stands quiet at first. Then he begins to scream.

In 1711, the Tuscarora Indians of North Carolina murdered John Lawson, sticking him all over with pitch pine splinters before setting him ablaze. At the time, Lawson may have been the best English friend the Tuscarora had. From his first encounters, he seems clearly to have respected them. And in his writings, he lauded their natural graces, admired their courage, and blamed his fellow Englishmen for their destruction.

Lawson's death was only the opening act of "the most deadly Indian war in North Carolina history" (Lefler and Newsome 27). When it ended in 1713, the Tuscarora as Lawson knew them were no more. Today, Lawson's book, A New Voyage to Carolina, remains our most reliable record of the Tuscarora and the other Indians of Carolina's Coastal Plain and Piedmont; his journals captured those cultures in prose just before they were wiped clean from their rivers and creekside settlements, leaving the rich soil salted with arrowheads that emerge in cottonfields after rain. To this day, farmers pick them up, slip them in their pockets, and ruminate over them, as if they are pieces of some compelling but unsolvable puzzle.

In May 1700, John Lawson, filled with the spirit of adventure, set sail for the New World, heading for North Carolina on the advice of a world traveler he had met by chance in England. By December, he had somehow garnered an assignment from the Lords Proprietors to survey the unknown lands of the Carolina interior. As he traveled, he collected plant specimens for a London botanist; he also kept a journal describing the New World plants and wildlife. Lawson wrote about them in such lush detail it's not surprising that a later plagiarism of his journal was entitled "The Newly Discovered Eden." But his most compelling records are those describing Eden's native inhabitants.

Gary Snyder says that when early explorers confronted wilderness and natural societies, they "had to give up something of themselves: they had to look into their own sense of what it meant to be a human being" (13). What he calls "the etiquette of the wild" requires that we "learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home" (24). Surely John Lawson did that; nearly three centuries after its publication, his story still makes fascinating reading, as it opens up for us the mysteries of the first North Carolinians.

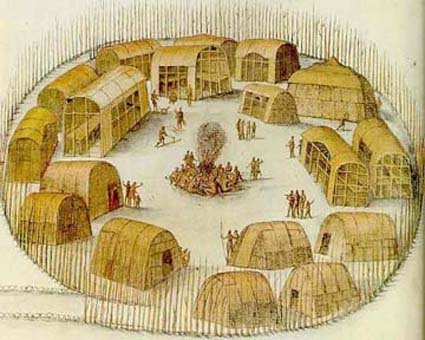

Lawson treats the Carolina Indians in two sections of his book. In the first, a narrative of his first walking trip through North and South Carolina, he introduces readers to successive nations as he encounters them. In his journal entries, each nation is freshly revealed as a discrete social and political unit, with physical differences, special foods and ceremonies, clothing and housing, tall tales and superstitions. In his last section, he lumps together these distinct nations into a general portrait, "An Account of the Indians of North Carolina," in which he draws from his eight years of continued study and travel from his new home in eastern North Carolina.

[Page 64]

On 28 December 1700, Lawson set off from Charleston, South Carolina on his 59-day pilgrimage into the heart of the Carolina frontier. He traveled light. Packed into a single huge canoe was all of his equipment - guns, powder, some food, a religious tract, his journal, blankets trinkets for trading - and all of his crew: a party of five Englishmen, three Indian men, and one Indian woman.

Lawson seems to have been the kind of fellow who pops out of the bedroll raring to go, rain or shine. On at least one occasion, he was ready two hours before his Indian guide. He rarely stopped to rest, leaving slowpokes to catch up as best they could at the end of the day. The group covered, on foot or in canoes, an average of 10 to 20 miles a day - 30 on a good day. They never lingered long, stopping a day or two at an Indian town, visiting and feasting with the chief, trading a bit, hunting up some food and a new guide, then traveling on. Between settlements, they camped out in the woods, dining alfresco, often on turkey or opossum stew. For "a thousand miles" (more like 500 as the crow flies), they followed rivers and trading paths, from the South Carolina coast to the Piedmont of North Carolina, in a crescent-shaped trail that eventually turned back east toward the ocean, concluding between Washington and Bath, by the Pamlico River. For virtually every river Lawson encountered, he also found an Indian nation with its own ruler and customs; often the nation would bear that river's name. The Santee, the Congaree, the Wateree, the Waxhaw, the Catawba, the Eno, the Meherrin, the Neuse, the Sapona, and the Pamlico - all were nations as well as waterways.

Lawson's reaction to the amazing peoples he encounters is remarkably respectful for his own time and culture. He shows particular interest in Indian food, social mores, marriage customs, burial practices, and medicine men. He compares the demure Indian wives' ways favorably to those of some sharp-tongued Englishwomen; he finds sexual etiquette among a number of tribes amusing but oddly sensible. Marriage, divorce, and sexual favors are generally matters of mutual consent; the women are sexually liberated. He calls the religious men outrageous liars, yet painstakingly records their useful herbs and cures as well as the strange phenomena they claim to control. The Waxhaw, Catawba, and Sapona nations seem to impress him the most. For the Tuscarora, he shows a wry sympathy and a healthy respect.

Full Article Here:

http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/exhibits/lawson/htmlFiles/TUSC.html

Related:

http://the-lost-colony.blogspot.com/search?q=john+lawson

© History Chasers

Click here to view all recent Searching for the Lost Colony DNA Blog posts