A year later, Columbus returned with 17 ships and 1,200 men to enlarge the settlement. But he found La Navidad in ashes. There were no inhabitants and no gold.

Over the years, many scholars and adventurers have searched for La Navidad, the prize of Columbian archaeology. It is believed to have been in Haiti. The French historian and geographer Moreau de Saint-Méry sought La Navidad there in the 1780s and '90s; Samuel Eliot Morison, the distinguished American historian and Columbus biographer, in the 1930s; Dr. William Hodges, an American medical missionary and amateur archaeologist, from the 1960s until his death in 1995; and Kathleen Deagan, an archaeologist at the University of Florida at Gainesville, in the mid-1980s and again in 2003.

And then there's Clark Moore, a 65-year-old construction contractor from Washington State. Moore has spent the winter months of the past 27 years in Haiti and has located more than 980 former Indian sites. "Clark is the most important thing to have happened to Haitian archaeology in the last two decades," says Deagan. "He researches, publishes, goes places no one has ever been before. He's nothing short of miraculous."

Moore first visited Haiti in 1964 as a volunteer with a Baptist group building a school in Limbé, a valley town about ten miles from the northern coast. In 1976, he signed on to another Baptist mission in Haiti, to construct a small hydroelectric plant at a hospital complex in the same town. The hospital's director was Dr. Hodges, who had discovered the site of Puerto Real, the settlement founded circa 1504 by the first Spanish governor of the West Indies. Hodges also had conducted seminal archaeological work on the Taino, the Indians who greeted Columbus. Hodges taught Moore to read the ground for signs of pre-Columbian habitation and to identify Taino pottery.

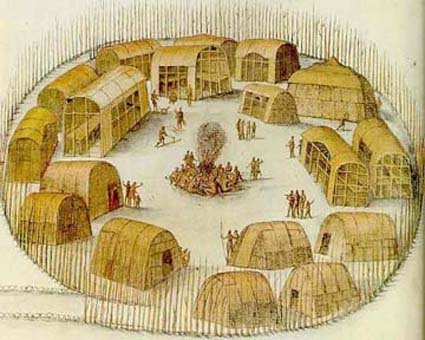

The Taino, who flourished from a.d. 1200 to 1500, were about 500,000 strong when Columbus arrived. They were reputedly a gentle people whose culture, archaeologists believe, was becoming more advanced. "Taino" means "noble" or "good" in their Arawak language; they supposedly shouted the word to the approaching Spanish ships to distinguish themselves from the warring Carib tribes who also inhabited Hispaniola, the island Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic. Male and female Taino chiefs ornamented themselves in gold, which sparked the Spaniards' avarice. Within a few years of Columbus' arrival, the Taino had all but vanished, the vast majority wiped out by the arduousness of slavery and by exposure to European diseases. A few apparently escaped into the hills.

For two decades Moore has traveled Haiti by rural bus, or tap-tap, with a Haitian guide who has helped him gain access to remote sites. Diminutive Haitian farmers watched with fascination as Moore, a comparative giant at 6-foot-2, measured areas in his yard-long stride and poked the soil with a stick. Often he uncovered small clay icons—a face with a grimace and bulging eyes—known to local residents as yeux de la terre ("eyes of the earth"), believed to date to Taino times and to represent a deity. Moore bunked where he could, typically knocking on church doors. "The Catholics had the best beds," Moore says, "but the Baptists had the best food."