Everything is Relative

By Jennifer Sheppard

Certificate in Genealogy

Professional Research Option

Brigham Young University

Provo, UT, USA

Mr. Powell is in the distinctive position to have written this book as he not only lives in England but is the retired Mayor of Bideford with access to never before published information regarding the voyages. He also possesses first hand knowledge of “Croatoan” having spent time where the colonists were said to have settled. This gives him a unique perspective on America’s greatest unsolved mystery.

I must confess, household chores and the like suffered greatly while I was reading this book because it was virtually impossible to put down! This work is concisely written, easy to read, brilliantly shared and exciting to say the least.

The introduction of the book sums it up beautifully, from which I quote: “The story of the first attempt to colonise America by the English nation is a story of extraordinary courage, despair, misfortune, joy and simple wonder……..prepare for an adventure no Hollywood producer could hope to conjure in their wild-est dreams, and remember, as you read, that this is a true story.”

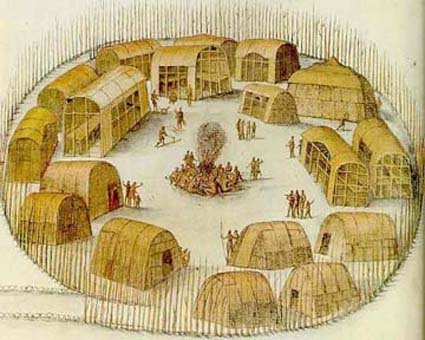

Mr. Powell leads us step by step, through the entire sequence of events undertaken to plant a permanent English settlement in what was to become the USA. He begins his book with a short biography of Sir Ri-chard Grenville, the “unsung hero” that is “unsung” no more. Some may not be aware that Grenville made more than one voyage to what was to become America and also served as “onetime Lord of the Manor of Bideford and was almost exclusively known for being the subject of an Alfred, Lord Tennyson poem…..”

Next, Andrew Powell covers “The Voyage of Amadas and Barlowe 1584 and The Voyage of Grenville 1585.” He moves on to include The Military Colony of 1585, Parts One and Two. Then he covers the “Voyages of 1586, The “Planters’ Colony of 1587,” “The Voyages of 1588,” “The deposition of Pedro Diaz 1585-1589,” “Raleigh’s Assignment of 1589,” and ends the transcriptions with “The Voyage of 1590. Subsequently he includes information unknown to have been published on the “ships and captains of Eng-land” involved in these voyages, without whose participation this amazing adventure would not have been possible.

And last but not least, Mr. Powell shares his own thoughts and analysis on “The Colonists,” including the types of expertise the people considered for this exploration, would have had to possess in order to survive and to thrive in their new lives in an unknown wilderness.

In the next chapter “Questions, Answers; Answers, Questions, he summarizes the “If Only’s’” revealing the possible “near misses” and “close encounters” that may have designated Croatoan as the first permanent English settlement in America rather than Jamestown. Mr. Powell ends his work with “The Hunt for The Lost Colony” wherein he provides never before published information uncovered by The Lost Colony Re-search Group, the Croatoan Archaeological Society, Professor Mark Horton of Bristol University and the author himself, Andrew Powell.

The footnotes containing detailed explanations of unfamiliar terms and words, found in the transcription of the original documents, are invaluable and much appreciated by the reader. This enables the reader to understand obsolete terms/words found in the journals he meticulously transcribed. As a genealogist who insists on working with primary sources whenever possible, this is certainly a plus and the fact that it is a true and accurate account of what actually happened make it a terrific read.

I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in the study of the so called “Lost Colony” and to those who truly enjoy reading a good non-fiction story which just happens to be some heretofore unknown history of what would one day become the United States of America!

The book is 302 pages, measures 8 X 5 inches, ISBN-10: 1848765967; ISBN-13: 978-1848765962 (Trou-bador Publishing Ltd © 2011, 5 Weir Road, Kibworth Beauchamp, Leicester, LE8 OLQ, WW.TROUBADOR.CO.UK). The book is also available at www.amazon.com for $16.78.

This blog is © History Chasers

Click here to view all recent Lost Colony Research Group Blog posts