William Strachey, first secretary of the Jamestown colony, wrote a history of that colony in 1612. In it, he mentioned several rumors about the fate of the colonists who had disappeared from Roanoke twenty years before.

Here Strachey explains the colonists’ attitudes toward the Indians, which are fortified by what they believe happened to their predecessors at Roanoke.

For the apter enabling of our selfes unto which so heavenly an enterprise, who will thinck yt an unlawfull act to fortefie and strengthen our selves (as nature requires) with the best helpes, and by sitting downe with guardes and forces about us in the wast and vast unhabited growndes of their[s], amongst a world of which not one foote of a thousand doe they either use, or knowe howe to turne to any benefitt; and therfore lyes so great a circuit vayne and idle before them? Nor is this any injurye unto them, from whome we will not forceably take of their provision and labours, nor make rape of what they dense and manure; but prepare and breake up newe growndes, and therby open unto them likewise a newe waye of thrift or husbandry; for as a righteous man (according to Solomon) ought to regard the lief of his beast, so surely Christian men should not shew themselves like wolves to devoure, who cannot forget that every soule which God hath sealed for himself he hath done yt with the print of charity and compassion; and therefore even every foote of land which we shall take unto our use, we will bargaine and buy of them, for copper, hatchetts, and such like comodityes, for which they will even sell themselves, and with which they can purchace double that quantity from their neighbours; and thus we will commune and entreate with them, truck, and barter, our commodityes for theires, and theires for ours (of which they seeme more faine) in all love and freindship, untill, for our good purposes towards them, we shall finde them practize violence or treason against us (as they have done to our other colony at Roanoak): when then, I would gladly knowe (of such who presume to knowe all things), whether we maye stand upon our owne innocency or no, or hold yt a scruple in humanitye, or any breach of charity (to prevent our owne throats from the cutting), to drawe our swordes, et vim vi repellere? (pp. 19–20)

Seven colonists, including a “young mayde,” apparently escaped the slaughter. The maid may have made a further escape.

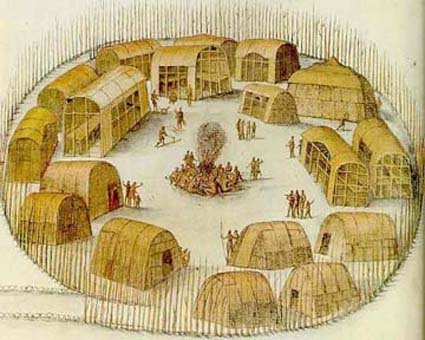

This high land is, in all likelyhoodes, a pleasant tract, and the mowld fruictfull, especially what may lye to the soward; where, at Peccarecamek and Ochanahoen, by the relation of Machumps, the people have howses built with stone walles, and one story above another, so taught them by those Englishe whoe escaped the slaughter at Roanoak, at what tyme this our colony, under the conduct of Capt. Newport, landed within the Chesapeake Bay, where the people breed up tame turkeis about their howses, and take apes in the mountaines, and where, at Ritanoe, the Weroance Eyanoco preserved seven of the English alive — fower men, two boyes, and one yonge mayde (who escaped and fled up the river of Chanoke [Chowan]), to beat his copper, of which he hath certaine mynes at the said Ritanoe, as also at Pamawauk are said to be store of salt stones. (p. 26)

Strachey explains what happened to the colonists after they left Roanoke.

[H]is majestie [James I] hath bene acquainted, that the men, women, and childrene of the first plantation at Roanoak were by practize and comaundement of Powhatan (he himself perswaded therunto by his priests) miserably slaughtered, without any offence given him either by the first planted (who twenty and od yeares had peaceably lyved intermixt with those salvages, and were out of his territory) or by those who nowe are come to inhabite some parte of his desarte lands, and to trade with him for some comodityes of ours, which he and his people stand in want of; notwithstanding, because his majestie is, of all the world, the most just and the most mercifull prince, he hath given order that Powhatan himself, with the weroances and all the people, shalbe spared, and revenge only taken upon his Quiyoughquisocks, by whose advise and perswasions was exercised that bloudy cruelty… (pp. 85–86)

continue here