The Tuscarora War was the most terrible Indian war that ever took place in North Carolina. The Indians struck in the autumn of 1711, and they could hardly have chosen a more advantageous time. The colonists were divided by political disagreement. Edward Hyde had come over from England the previous year to administer the colony as deputy governor. His right to the post was disputed by Thomas Cary who had previously held the office. In the dispute that followed, known as Cary's Rebellion, Hyde and Cary both attracted supporters who actually took up arms against each other. The colony was in the midst of civil war.

The Rebellion ended in the summer of 1711, but there was already evidence of serious unrest among the Indians. At the beginning of the year, the Meherrin had been reported as becoming more and more insolent. By mid-summer this attitude had spread to other tribes. At the same time, it was said that Cary supporters had offered rich rewards to the Tuscarora to attack the followers of Hyde. It was also said that the young men of the tribe had agreed to the offer but had been overruled by the old men. This latter report seems to have lulled the settlers into a false sense of security.

According to one prominent colonist, the increasing hostile attitude of the natives was because the whites "cheated these Indians in trading, and would not allow them to hunt near their plantations, and under that pretense took away from them their game, arms and ammunition." A more immediate cause might have been the founding of the town of New Bern in 1710 by Baron Christoph von Graffenried, the leader of a group of Swiss and Germans settling the area.

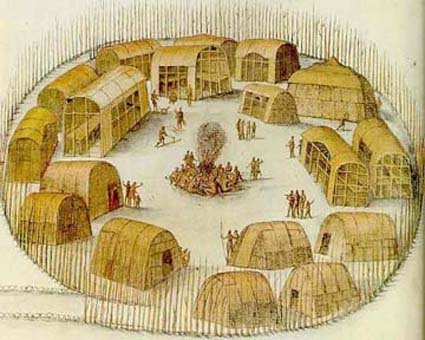

New Bern was established on the site of a Neusioc Indian town called Chattooka, or Cartouca. The natives who occupied the land were paid for it and they moved away, but apparently they were not satisfied. As Surveyor-General of the colony, John Lawson surveyed the site. According to von Graffenried, the site had also been chosen for him by Lawson who claimed it to be uninhabited. When it was found to be occupied by Indians, he charged the Surveyor-General with recommending they be driven off without payment. These accusations were not in keeping with Lawson's otherwise sympathetic attitude towards the natives, but, if true, they might explain the terrible fate he met soon thereafter.

In mid-September, 1711, Lawson invited von Graffenried to go with him on a trip up the Neuse. The purpose of the trip was to examine the river and to seek a better route to Virginia. Lawson assured the Baron there would be no danger from the Indians, but the prospect of such a route through, or near, their hunting grounds could have been a matter of great concern to the Indians. In any event, several days after their departure, both men were seized by the natives and taken to Catechna, the Tuscarora town of King Hancock, on Contentea Creek. After questioning the prisoners, the Indians decided to set them free. Before they were to leave the following day, the captives were questioned again. The King of Cartouca, the New Bern site, reproached Lawson who answered in anger. A general quarrel followed in which von Graffenried did not take part, but both he and Lawson were again confined. At another council meeting, the Indians decided to execute Lawson and to free the Baron who had promised presents for his freedom. Von Graffenried did not see it and the natives were very secretive about the manner of Lawson's death. Some said he was hanged and others said his throat was slit with a razor he carried with him. It was generally believed the Indians "stuck him full of fine small splinters of touchwood, like hogs' bristles, and so set him gradually on fire."