Historic Edenton, North Carolina

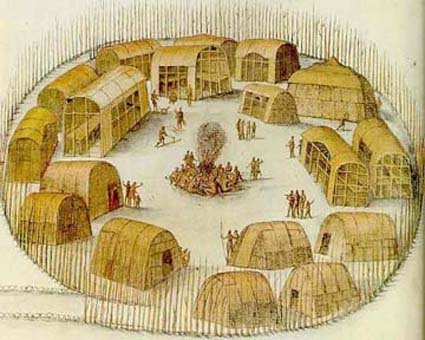

The exact year of the settlement of what is now Edenton will probably never be known, but as far back as 1658* intrepid adventurers from the Jamestown neighborhood, drifting down the eastern streams and hewing a path otherwise through the wilderness from Virginia, effected a location on the bank of a natural harbor of exquisite beauty, the site of the future Edenton. Many, many years before, maybe a century prior, Amadas and Barlow, explorers from one of the initial Raleigh expeditions, entered the waters of the Chowan river, they reported, where they found an established colony of Indians, numbering 800 and known as the Chowanokes. Their stories of their travels were vague, but from the hardy pioneers of the northland there was no uncertainty.

So here in this region was established the first permanent settlement in North Carolina, the "mothertown" of the State. Edenton at once became the focal point of civilization in the Province, the capital of the Colony and the home of the Royal Governors. Supposedly incorporated in 1715 as "The Towne on Queen Anne's Creek," and running through a subsequent diversity of titles such as "Ye Towne on Mattercommack Creek" and "The Port of Roanoke," in 1722 the spot was named Edenton in honor of Governor Charles Eden.

"Here," wrote an early historian, "was a colony from civilized life, scattered among the forests, resting on the bosom of nature, with absolute freedom of conscience and where benevolent reason was the simple rule of its conduct."

And here, wrote Lawson in 1708, "the fame of this new discovered summer country spread through the other colonies and in a few years drew a considerable number of families thereto, who all found land enough, and that which was very good and commodiously seated both for profit and pleasure."

"The women have brisk and charming eyes," commented Lawson further descriptively of the small primal population, "which sets them off to good advantage. They marry very young, some at 13 or 14, and she that stays 'til 20 is reckoned a very indifferent character; as for the men they are commonly of a bashful, sober behavior but are kind and hospitable to all that come to visit them."

The records are clear that as the first settlers grounded their rude craft on the shores of the beautiful Albemarle Bay upon which Edenton is situated, an almost impenetrable wilderness confronted them and defied their early attempts at colonization, but with steadfast perseverance and determination they wrested from nature and the Red Men a foothold from which North Carolina has sprung and built itself a place in the commonwealth of states

Across the little settlement, as at the pioneer colony on Roanoke Island, was thrown a high timbered and palisaded fence with entrance gates defended by a rude fort. At night, perhaps, eagle-eyed riflemen kept constant watch for Indians, and the repeated cry "All's Well" fell as a soothing benediction upon the ears of the brave villagers, exhausted no doubt from the day's labor of erecting homes and clearing woodlands. Frequent attacks were made by the Indians, but soon after 1712 a treaty of peace, still preserved in its original form on parchment, was made whereby the Aborigines withdrew to other lands. A phrase from this treaty sets forth "That there be firm, perpetual and inviolable peace to continue as long as the sun and moon endure between all and every the inhabitants and people of North Carolina and all the nation and people of the Tuscaroroe Indians-- that there be always a friendly and amicable correspondence between the said English and Tuscaroroe Indians."

From the very nature of the struggles and hardships endured by this little community it was but natural that a passionate love of freedom and liberty should have taken deep root here, and history confirms the fact that resistance to British authority existed here one hundred years before the Revolution, and that the frequent rebellions and early disturbances in this section were nothing less than resistance to illegal and usurped power, and evidenced a contest for political and religious independence. These were but long shadows cast before the Mighty Revolution and permits this little colony to be styled one of the first birthplaces of that epochal struggle.

From its very beginning to the time when freedom from England was finally achieved Edenton was a hot-bed and center of continuous revolt and resistance to the Crown. Unjust, oppressive taxes, land rents, cruel and unusual punishments for crime, kept the community in constant turmoil, and the records of these stirring times reflect the grim determination of the people to throw off the domination of the British and gain for themselves that new freedom for which they had braved the many hardships and dangers incident to the settlement of this new land. Countless are the references in the Colonial Records of North Carolina as to the truth of these assertions, and the small town warfares and oppositions on the streets of Edenton and about its "Publick Parade," as its present day Commons was originally called, are reported with freedom and much candor.

These disputes, actually the growing pains of a people trying to be free, kept the jail overcrowded, the stocks, the rack, the pillory and the ducking stool, well overworked. Such smoulderings of discontent and discord broke into vivid flame on August 22, 1774, when a mass meeting of citizens, presided over by the fiery Daniel Earle, rector of St. Paul's Church, gathered at the court house, publicly denounced the unjust imposition of taxes and prosecutions and condemned the Boston Port Act, openly declaring that "the cause of Boston was the cause of us all." Quickly followed on October 25 of the same year the famous Edenton Tea Party, particularized elsewhere, when 51 ladies of the town met and openly resolved that "We, the Ladys of Edenton, do hereby solemnly engage not to conform to the Pernicious Custom of Drinking Tea," or that "We, the aforesaid Ladys will not promote ye wear of any manufacturer from England until such time that all acts which tend to enslave our Native country shall be repealed."

And in furtherance of this attitude of protest and a month or more prior to the Continental Congress's Declaration of Independence, the Vestry of St. Paul's Church, in a written document called "The Test," added an ecclesiastical note of protest in this wise--"We, the subscribers, professing our allegiance to the King and acknowledging the constitutional executive power of Government, do solemnly profess, testify and declare that we do absolutely believe that neither the Parliament of Great Britain nor any member of a constituent branch thereof, have a right to impose taxes upon these colonies to regulate the internal policy thereof; that all attempts by fraud or force to establish and exercise such claims and powers are violations of the peace and security of the people and ought to be resisted to the utmost, and that the people of this Province, singly and collectively, are bound by the Acts and Resolutions of the Continental and Provincial Congresses, because in both they are freely represented by persons chosen by themselves. And we do solemnly and sincerely promise and engage under the sanction of Virtue, Honor and the Sacred Love of Liberty and our Country, to maintain and support all and every the Acts, Resolutions and Regulations of the said Contintental and Provincial Congresses to the utmost of our power and ability."

Then came the Revolution and Edenton was ready through the leadership of her illustrious sons of that period to take her stand at the forefront among the towns of the entire nation to add her services in the cause of freedom. "Within the vicinity of Edenton," says a writer, "there was in proportion to its population a greater number of men eminent for ability, virtue and erudition than in any other part of America." Another writer said: "there are but few places in America which possess so much female artillery as Edenton," referring, of course, to the action of the ladies of the Tea Party. The military leaders numbered General Edward Vail, Colonel Thomas Benbury and Colonel James Blount and many others, who raised company after company and marched off to aid Washington.

Joseph Hewes, a Signer of the Declaration of Independence, was a citizen of Edenton, a large ship-owner and merchant, who carried on a great trade with England and the West Indies. War meant a tremendous financial sacrifice to Hewes but, true patriot that he was, he signed the Declaration and put his entire fleet at the disposal of the Continental forces. To Hewes the Nation is indebted for the brilliant services of John Paul Jones. Hewes who was Secretary of the Naval Affairs Committee of the Continental Congress and virtually the first Secretary of the Navy, was directly responsible for the elevation of Jones to his position in the new Navy. Jones never forgot his patron and sponsor and many letters are extant telling of the great gratitude he felt for Hewes' interest in him. "You are the Angel of my happiness; since to your friendship I owe my present enjoyments, as well as my future prospects. You more than any other person have labored to place the instruments of success in my hands." Hugh Williamson, celebrated physician, was another worthy son of Edenton during the Revolution. Dr. Williamson, at his own expense, fitted out ships with supplies for the American Army, was Surgeon-General of the State Colonial troops and rounded out a brilliant career by signing the Constitution of the United States in 1787.

Samuel Johnston of Edenton was another nationally known patriot during these stirring times. He was a leader in the movement for freedom and was the first United States Senator from North Carolina. James Iredell, brother-in-law of Governor Johnston, was the political leader of this community for many years. After distinguished services to his country otherwise he was appointed by George Washington to the Supreme Court of the United States. His opinions were famous in the field of jurisprudence and he was considered one of the outstanding jurists of his time.

During its long history of nearly three centuries Edenton naturally has passed through many vicissitudes of fortune. Fires, storms and other calamities have taken their toll during the years but probably no one occurrence threw such an apprehension of certain doom into its inhabitants as on a morning of April, 1781, when 80-year-old Jeremiah Mixson, the town crier, shrilled the clarion news to the inhabitants that Cornwallis was sending forces south from Suffolk to burn Edenton in revenge for the part Edenton had played in fomenting the resistance to British authority. Panic ensued. People ran to and fro not knowing what to do. Alarms were sounded, bells of the town were rung and everyone congregated on the Green seeking some way to escape the impending peril. Resistance was out of the question as practically the entire male population was away in Washington's army. Soon a messenger arrived by boat from Windsor, where Edenton's danger from British attack had become known. He offered the people of Edenton refuge in his Bertie County town. The proffer was accepted eagerly and thankfully and by dawn Edenton was deserted. No living human or animal was left in town. For seven days the community was like a city of the dead. Then came better news. Cornwallis, hard pressed, was having his own troubles. His Suffolk forces were recalled, the intended invasion fell flat, and the people of Edenton returned rejoicingly to their homes and carried on.

Then came the Civil War, with its attendant suffering and reconstruction. Edenton as had been its custom for over two hundred years, patriotically threw itself into the fray and sent several units to fight for the southern cause. Among these was its famous Edenton Bell Battery, whose field pieces, as in countless other sections of the south, were cast from the town bells in response to a general call to do so sent throughout the Confederacy and which was immortalized in a war Iyric by F. Y. Rockett. The Edenton Bell Battery was organized in 1862 by Captain William Badham and was engaged in many battles throughout the war, finally surrendering to Sherman in 1865.

Although now a modern city, Edenton is fortunate in having preserved many old buildings rich in their association with Colonial times, and the visitor finds here today numerous spots of historic interest carefully kept in their original setting.

Among the priceless buildings here is the Court House, erected in 1767. The oldest Court House in North Carolina, and is an architectural gem of national reputation. A sketch of its life reads like a panoramic review of the life of North Carolina: the hardships of the early colony, the struggles of revolution, civil war and reconstruction; all finally unfolding into the commonwealth that is the Old North State of today. Through six conflicts the call to arms has resounded within its walls; it can recall the inauguration of every President of the United States; Governors from the time of Josiah Martin have spoken from its rostrum; Princes and Presidents have danced on its floors and the most illustrious lawyers of the State have pleaded their causes before its bar.

On the second floor is the famous panelled room, long used in the old days as a town social center. Also on the second floor is the lodge-room of the Masons, containing among other priceless relics, the chair used by George Washington in the lodge at Alexandria, Virginia.

The oldest corporation in North Carolina, St. Paul's Parish, was formed in 1701 and immediately erected a small wooden chapel on the shores of the sound on "Hayes" plantation. This was the first church in the State. We have it on the authority of the Rev. Mr. Rainsford, one of the early ministers, that this first edifice proved inadequate to accommodate the large congregations attending his sermons and he wrote that on many occasions he was compelled to hold his meetings out in the open, under the trees. Consequently, a second building was constructed, and the third, the present magnificent pile, St. Paul's, was begun in 1736. It is known as the "Westminster Abbey" of North Carolina, and beneath its ancient oaks sleep scores of the founders of our commonwealth.

"Bandon," situated on the Chowan River, 15 miles above Edenton, was the former home of Rev. Daniel Earle, who established there the first classical school for boys in North Carolina, the initial school having been founded at a spot called Sarum, near the Gates County line. Daniel Earle, affectionately called "Parson" Earle was rector of St. Paul's, Edenton, during the Revolutionary period and a fiery patriot.

The "Cupola House", built in 1758 by Francis Corbin, land agent of Lord Granville in Carolina, now houses the Edenton Museum and the Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library.

The outstanding colonial home of the entire State of North Carolina is the magnificent seat of Governor Samuel Johnston. Situated in the midst of its one thousand fertile acres and overlooking Edenton Bay, "Hayes", a pure American type, is a treasure-house of early Americana. Priceless portraits adorn its walls and its library of thousands of old volumes and manuscripts contains many rare "first editions."

"Beverly Hall", the old State Bank from 1811 to 1836, is now used as a residence. Its huge secret vault, encased in steel, and its key, weighing two pounds, are reminders of the cumbersome banking equipment of an older day.

Eastward from Hayes and stretching along the North Shore of Albemarle Sound lie other fine old estates and homes, including "Montpelier", "Atholl", "Mulberry Hill", "Greenfield", and others.

Many other objects and places of interest attest Edenton's association with the making of the Commonwealth. Some of these are the Revolutionary cannon brought from France and now mounted on Edenton's "Battery" at the foot of the Courthouse Green; the site of the famous Edenton Tea Party, marked by a Colonial teapot mounted on a Revolutionary cannon; the homes of Judge Iredell, Governor Iredell, the Littlejohn house and the Civil War fort at "Wingfield" on the Chowan River.

And such is and was the new-old Edenton: proud of her past and progressive for the future; democratic, yet dignified; pressing forward for a newer, better life, yet mindful of the experiences of the years; and ever clinging to all ancient things that are of good report, she moves to her destiny of a newer day.

Edenton, North Carolina. In This Booklet Edenton Invites Your Atention to its Historical Attractions and its Advantages for Industry and Agriculture. Edenton, NC: The Chowan Herald Print, 1937.

* Some say Edenton, NC was the second English Colony, an honor that usually goes to Jamestown. Could these "English" have been the "Blue Eyed Indians", mixed blood descendants of the Lost Colonists?Reader comments welcome.

For those of you who knew Edenton existed, did you know the original residents were the Algonquian speaking Chowanac and Weapemeoc (don't ask me to pronounce that) Indians? That it was the first permanent European colony settled (not counting the lost colony of Roanoke)? That it was the first colonial capital of North Carolina? That famous residents include signers of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution? That it was first called "The Towne of Queen Anne's Creek"? We didn't until we watched a 15-minute video at the Visitors Center where we loaded up on brochures.