On their third day in the New World, sometime in July 1584, Sir Walter Ralegh's reconnaissance party under Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe met three natives. Having no language in common, the two groups quickly resorted to the universal media of polite discourse: food and drink. The explorers took an Indian aboard one of their ships and persuaded him to sample their meat and wine, which Barlowe said, "he liked very well." In return, the Indian caught them as many fish as his canoe could hold.

Over the next few days the Englishmen entertained Granganimeo, an Indian nobleman, and some of his retinue. He reciprocated by sending "euery daye a brase or two of fatte Buckes, Conies [common cottontail rabbits], Hares [marsh rabbits], Fishe....fruites, Melon [pumpkins], Walnuts, Cucumbers [probably squash], Gourdes, Pease, and diuers rootes." Barlowe made special note of the Indians' corn, which he found "very white, faire, and well tasted."

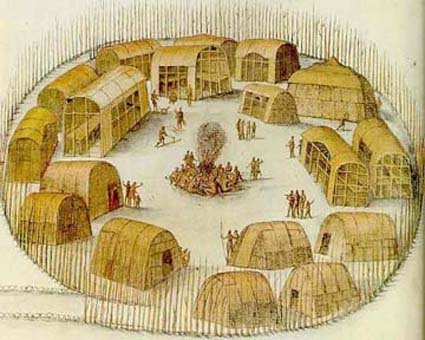

At length Barlowe and seven other Englishmen visited the palisaded village on the north end of Roanoke Island. Although they seem to have arrived unexpectedly while Granganimeo was elsewhere, they got a taste of local hospitality. After washing the visitors and their clothes, Granganimeo's wife and retainers served the Englishmen a feast in his five-room house. It included roasted and stewed venison and fish, boiled corn or hominy, raw and cooked pumpkins and squash, and various fruits.

Barlowe did not record what beverages the Indians served him and his companions, but he did say that the Indians customarily drank wine "while the grape lasteth" and water "sodden with Ginger [sic] in it, and blacke Sinamone [perhaps dogwood or magnolia bark], and sometimes Sassafras, and diuers other wholesome, and medicinable hearbes." (Black drink, made mostly or exclusively of scorched yaupon leaves, was common throughout the region, but the spiced beverages Barlowe describes were not, and wine, if he was not mistaken, was probably unique in the Western Hemisphere.)

For safety Barlowe and company declined to sleep in the village and spent a rainy night in open boats in the sound. Their hosts evidently took no offense, for they sent along the leftovers, pots and all, and kept watch on shore.

Not until Ralph Lane and his colonists spent eleven months in North Carolina (1585-1586) did Englishmen begin fully to appreciate the bounty of the region and the diversity of Indian cuisine. John White, who may not have stayed in the New World the whole time, made several revealing drawings of Indians cooking and eating. Thomas Harriot, a colonist with an analytical mind and a discriminating palate, devoted much of his "Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia" to a catalog of native foodstuffs.

The waters of the region yielded tremendous quantities of fish-sturgeon, herring, mullet, and other species-upon which the Indians depended for much of their protein. Crabs, oysters, clams, scallops, and mussels were another major part of their diet. In spring, when stores laid in the previous fall were depleted and crops were not yet ripe, tribes living on the outer coastal plain often sent members who could be spared to nearby estuaries to subsist on shellfish. (In the spring of 1586, worsening relations with the Indians upon whom the colonists depended for food forced Ralph Lane to adopt this practice and disperse his band to various locations where fish and shellfish could be obtained easily.) Over generations, huge mounds of shells accumulated at favored spots. One of these, the present Tillett site on the south end of Roanoke Island, shows evidence of use from around the time of Christ to the disappearance of the coastal tribes in the seventeenth century. Harriot mentioned turtles and terrapins (both "very good meate, as also their egges" ), porpoises, and "Creuises" (crayfish or lobsters or both), but did not say whether Indians ate them.

The Indians of eastern North Carolina probably had no domestic animal except the dog, but the vast forests, marshes, and swamps abounded in bears, deer, rabbits, squirrels, turkeys, doves, partridges, and water birds. Several of the nominally edible mammals were entirely new to the Englishmen, and Harriot did a poor job of describing them. Saquenuckot, for example, could have been a muskrat, opossum, mink, or raccoon; so could Maquowoc.

Harriot listed six wild root vegetables eaten by the Indians. Openauk may have been the ground nut or the Indian or marsh potato-not the Irish potato. (Sir Walter Ralegh has long received undeserved credit for bringing the Irish potato to Europe. It is native to South America, and the Spanish probably introduced it before he was born.) Okeepenauk, "of the bignes of a mans head," may have been the wild potato, a relative of the sweet potato. The English identified coscushaw as casasava. If it belonged to the arum family, it was not poisonous like raw cassava; but the Indians' elaborate preparation probably made a considerable improvement in its taste. Harriot thought that tsinaw (probably some kind of smilax) was similar to the "China root" imported to England from the East Indies. Its name may be nothing more than a native's attempted pronunciation of China. Harriot had such a low opinion of kaishucpenauk (duck potatoes?) that he pointedly omitted "their place and manner of growing." He said little more about the hot-tasting habascon, perhaps the cow parsnip, except that the Indians added it to their stewpots for flavoring and never ate it alone.

Wild fruits added further zest and balance to the Indians' varied diet. Strawberries were available for the taking, as were crab apples, mulberries, persimmons, prickly pears, "Hurtleberies" (huckleberries, blueberries, or even cranberries), and many species that Harriot did not list. The Indians undoubtedly ate all four native varieties of grape (Harriot mentioned two) out of hand even if they did not make wine. In addition, the Indians collected many nuts and seeds, including chinquapins, two kinds of "walnuts" (probably the black walnut and one or more sorts of hickory nut), the five kinds of acorn that Harriot could distinguish (and perhaps others), and a grain that sounds like wild rice but probably came from an unrelated marsh grass.

Full Article Here:

http://www.nps.gov/archive/fora/indcooking.htm