Sunday, June 15, 1997

After unearthing artifacts from two living room-sized sand pits, archaeologist David S. Phelps may well be on the trail of the famed ``Lost Colony'' of Roanoke Island.

Phelps, director of East Carolina University's Coastal Archaeology Office, has been digging on North Carolina's Outer Banks for more than a decade. This spring his team uncovered objects that could indicate that at least a few of the first English settlers in America who mysteriously disappeared from Sir Walter Raleigh's colony migrated south onto Hatteras Island.

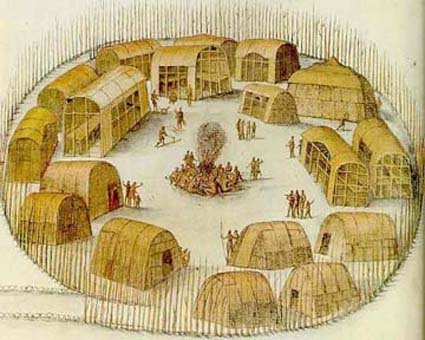

Colonists who left the Fort Raleigh area between 1587 and 1590 may have mingled with the Croatan Indians, whose capital was the present town of Buxton - now the home of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

``The Native Americans of this area were at least trading artifacts with the English - if not living with some of the Lost Colonists,'' Phelps said Thursday from alongside one of the 8-foot-deep dig sites. ``We found much more than we'd hoped to here. This is certainly part of the Lost Colony story.''

Handmade lead bullets, pieces of white and red clay pipes, a leather clasp, fragments of European pottery and even a nickle-sized corroded brass or copper coin with a tiny hole drilled in each end are among Phelps' favorite finds from the recent dig. The coin, he said, is similar to a 1563 coin found on Roanoke Island, about 50 miles to the north.

His team also discovered two fire hearths where Phelps said American Indians and colonists may have manufactured weapons and tools together.

Bill Kelso, who directs Jamestown's Rediscovery archaeological project near Williamsburg, Va., said he is ``very excited'' about Phelps' finds.

``It is entirely possible that some of the Lost Colonists went in that direction, toward Hatteras,'' Kelso said Friday. ``That may have been why they left that word `CROATOAN' carved in the tree. We really have no information about European artifacts found in America that date to the 16th century.

``I'd really love to see what Dr. Phelps has found.''

The ``Lost Colony'' legacy began in 1584 when Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe first explored North America for England's Queen Elizabeth. Outer Banks History Center curator Wynne Dough said there is ``considerable controversy over where Amadas and Barlowe first set foot on land. Some say it was between Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout.''

Those men never set up camp in America. But the next year, Englishman Ralph Lane led an expedition back to the Outer Banks to establish an encampment on Roanoke Island. Capt. John White organized Raleigh's colony of 117 men, women and children the following year - in 1587.

Colonists were supposed to establish a permanent settlement on Roanoke Island. White returned to England for supplies later that year. But war broke out in Europe and he didn't return to America until 1590.

By then, all of the colonists had disappeared.

Full Article Here:

SORRY THIS LINK NO LONGER WORKS AS IT DID WHEN I FIRST WROTE THIS ARTICLE

http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/VA-news/VA-Pilot/issues/1997/vp970615/06160222.htm