By Janet Crain

Many people do not know what it really meant to be an indentured servant when this country was a British colony. They imagine an agreement was made between two adults that in return for the cost of transportation here, the indentured servant would work a period of time, usually 7 years, in return for his or her debt. At first a small acreage was even awarded along with a sum of money and suit of clothes. That was soon phased out. There were many opportunities for the exploitation of this system and most were employed. It became common for people including children to be kidnapped (kid nabbed). The courts sent many persons convicted of crimes large and small to the colonies. Poor children were sent so that they not be a burden on the government. Young women and men were tricked aboard or knocked in the head and carried on board. It made no difference once the ship set sail. They were cut off forever from their friends and families.

Conditions on board were terrible. The ship's captains transported as many as possible, as cheaply as possible, and sold their indentureships once in the colonies. No attempt was made to keep families together. Conditions in the new country were so horrible that as many as 4 out of 5 soon died.

Eventually conditions became so bad that some of these people banded together and rebelled. It was called "Bacon's Rebellion".

Some call this the first stirrings of the eventual American Revolution.

Persons of Mean and Vile Condition

In 1676, seventy years after Virginia was founded, a hundred years before it supplied leadership for the American Revolution, that colony faced a rebellion of white frontiersmen, joined by slaves and servants, a rebellion so threatening that the governor had to flee the burning capital of Jamestown, and England decided to send a thousand soldiers across the Atlantic, hoping to maintain order among forty thousand colonists. This was Bacon's Rebellion. After the uprising was suppressed, its leader, Nathaniel Bacon, dead, and his associates hanged, Bacon was described in a Royal Commission report: He was said to be about four or five and thirty years of age, indifferent tall but slender, black-hair'd and of an ominous, pensive, melancholly Aspect, of a pestilent and prevalent Logical discourse tending to atheisme... . He seduced the Vulgar and most ignorant people to believe (two thirds of each county being of that Sort) Soc that their whole hearts and hopes were set now upon Bacon. Next he charges the Governour as negligent and wicked, treacherous and incapable, the Lawes and Taxes as unjust and oppressive and cryes up absolute necessity of redress. Thus Bacon encouraged the Tumult and as the unquiet crowd follow and adhere to him, he listeth them as they come in upon a large paper, writing their name circular wise, that their Ringleaders might not be found out. Having connur'd them into this circle, given them Brandy to wind up the charme, and enjoyned them by an oath to stick fast together and to him and the oath being administered, he went and infected New Kent County ripe for Rebellion.

Bacon's Rebellion began with conflict over how to deal with the Indians, who were close by, on the western frontier, constantly threatening. Whites who had been ignored when huge land grants around Jamestown were given away had gone west to find land, and there they encountered Indians. Were those frontier Virginians resentful that the politicos and landed aristocrats who controlled the colony's government in Jamestown first pushed them westward into Indian territory, and then seemed indecisive in fighting the Indians? That might explain the character of their rebellion, not easily classifiable as either antiaristocrat or anti-Indian, because it was both.

And the governor, William Berkeley, and his Jamestown crowd-were they more conciliatory to the Indians (they wooed certain of them as spies and allies) now that they had monopolized the land in the East, could use frontier whites as a buffer, and needed peace? The desperation of the government in suppressing the rebellion seemed to have a double motive: developing an Indian policy which would divide Indians in order to control them (in New England at this very time, Massasoit's son Metacom was threatening to unite Indian tribes, and had done frightening damage to Puritan settlements in "King Philip's War"); and teaching the poor whites of Virginia that rebellion did not pay-by a show of superior force, by calling for troops from England itself, by mass hanging.

Violence had escalated on the frontier before the rebellion. Some Doeg Indians took a few hogs to redress a debt, and whites, retrieving the hogs, murdered two Indians. The Doegs then sent out a war party to kill a white herdsman, after which a white militia company killed twenty-four Indians. This led to a series of Indian raids, with the Indians, outnumbered, turning to guerrilla warfare. The House of Burgesses in Jamestown declared war on the Indians, but proposed to exempt those Indians who cooperated. This seemed to anger the frontiers people, who wanted total war but also resented the high taxes assessed to pay for the war.

Times were hard in 1676. "There was genuine distress, genuine poverty.... All contemporary sources speak of the great mass of people as living in severe economic straits," writes Wilcomb Washburn, who, using British colonial records, has done an exhaustive study of Bacon's Rebellion. It was a dry summer, ruining the corn crop, which was needed for food, and the tobacco crop, needed for export. Governor Berkeley, in his seventies, tired of holding office, wrote wearily about his situation: "How miserable that man is that Governes a People where six parts of seaven at least are Poore Endebted Discontented and Armed."

His phrase "six parts of seaven" suggests the existence of an upper class not so impoverished. In fact, there was such a class already developed in Virginia. Bacon himself came from this class, had a good bit of land, and was probably more enthusiastic about killing Indians than about redressing the grievances of the poor. But he became a symbol of mass resentment against the Virginia establishment, and was elected in the spring of 1676 to the House of Burgesses. When he insisted on organizing armed detachments to fight the Indians, outside official control, Berkeley proclaimed him a rebel and had him captured, whereupon two thousand Virginians marched into Jamestown to support him. Berkeley let Bacon go, in return for an apology, but Bacon went off, gathered his militia, and began raiding the Indians.

Bacon's "Declaration of the People" of July 1676 shows a mixture of populist resentment against the rich and frontier hatred of the Indians. It indicted the Berkeley administration for unjust taxes, for putting favorites in high positions, for monopolizing the beaver trade, and for not protecting the western formers from the Indians. Then Bacon went out to attack the friendly Pamunkey Indians, killing eight, taking others prisoner, plundering their possessions.

There is evidence that the rank and file of both Bacon's rebel army and Berkeley's official army were not as enthusiastic as their leaders. There were mass desertions on both sides, according to Washburn. In the fall, Bacon, aged twenty-nine, fell sick and died, because of, as a contemporary put it, "swarmes of Vermyn that bred in his body." A minister, apparently not a sympathizer, wrote this epitaph: Bacon is Dead I am sorry at my heart,

The rebellion didn't last long after that. A ship armed with thirty guns, cruising the York River, became the base for securing order, and its captain, Thomas Grantham, used force and deception to disarm the last rebel forces. Coming upon the chief garrison of the rebellion, he found four hundred armed Englishmen and Negroes, a mixture of free men, servants, and slaves. He promised to pardon everyone, to give freedom to slaves and servants, whereupon they surrendered their arms and dispersed, except for eighty Negroes and twenty English who insisted on keeping their arms. Grantham promised to take them to a garrison down the river, but when they got into the boat, he trained his big guns on them, disarmed them, and eventually delivered the slaves and servants to their masters. The remaining garrisons were overcome one by one. Twenty-three rebel leaders were hanged.

That lice and flux should take the hangmans part.

To be Cont.

http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/zinnvil3.html

Friday, July 4, 2008

Persons of Mean and Vile Condition

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

7/04/2008 09:02:00 PM

![]()

Labels: colonies, indentured servant, transportation

Monday, November 5, 2007

Descendants of the 'Lost Colonists' Forced to Flee Their Own Homes

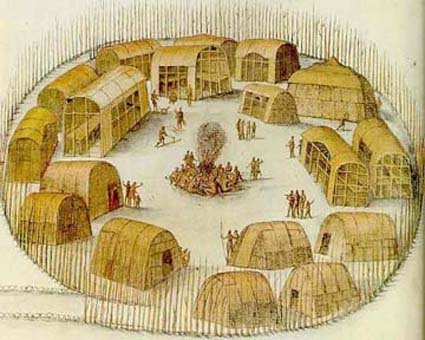

Cartuca was the capital of the people whose ancestors were known to Raleigh's colonists as Croatans. That the people of King Tom Taylor of Cartuca were descended from members of the Lost Colony may be concluded from the Congressional Report of 1914-1915, by Special Indian Agent O.M. McPherson. It precluded their classification as "Native Americans," with the benefits they would derive from this status. Hugh and Clement Taylor were both members of the Lost colony, but it is not known which, if either, was an ancestor of King Taylor.

When John Lawson and Baron De Graffenried conspired and contracted for the settlement of Palatines in the geographically strategic site of Cartuca--now New Bern--in 1710, the people of King Taylor were pleased at the prospect of European neighbors. Their king was maternally descended from Sir Manteo (knighted Lord of Roanoake and Dasamonguepeuk by Queen Elizabeth) and an english adventurer named Taylor, and they were pleased at the prospect of European neighbors.

The Palatines, from the border electorate of European kings, between France and Germany, had other plans, however. They had no intentions of allowing the Indians to remain in the area of the junction of the Trent and Neuse Rivers. The site controlled heavy freight traffic to the land's interior. With a few well-placed cannons De Graffenried could control shipping there as surely as his ancestors (cousins to the English royalty) controlled the junction of the Neckar and the Rhine.

The sale of Cartuca (Core Tucka, the new Currituck)was a momentous event for the Indians. They saw it as the beginning of a new way of life for them. What sort of a new way of life was soon to become clear to them as the mysterious Corees, who became extinct.

On the night of the celebration of the sale of Cartuca to the whites, it became clear to King Taylor that John Lawson had bargained away far more than Taylor ever intended to sell. His first awareness of the real extent of his peoples' loss brought from him an eloquent plea for brotherhood and cooperation between the whites and the Indians, in the English dialect of the Raleigh colonists.

The unaccustomed spectacle of a savage in European clothing, presenting an impassioned plea for unity with the Europeans, was more than one of the Palatines could take. Michel, a geologist and mining expert, raging drunk on raw rum, jumped on King Taylor and pummeled him mercilessly.

Such behavior on such an occasion was inconceivable to the Indians. To even interrupt a tribal chief was a capitol offense, at the chief's discretion. Michel's brutality ended the festivities for the natives of Cartuca. When Michel was pulled from the battered and bleeding Taylor, John Lawson delivered an ultimatum to the Indians. They must immediately leave Cartuca--and the surrounding area!

The shock to the Indians was profound. The loss to them was suddenly clear. Their home, with its wattled Welsh peasant style houses was no longer theirs. They were expected to vacate Cartuca immediately!

After his painful humiliation before the assembly of whites and his people, King Taylor raged in drunken indignation and disbelief in his own cabin. He rambled on about his white ancestry. He spoke of the nobility of his Indian ancestors, and the appreciation shown to them by the Virgin Queen. And he moaned his grief that John Lawson and the Palatines were such ungracious subjects of a sovereign who succeeded her.

As King Taylor rambled on, loudly and bitterly, English settlers and their friendly Tuscarora neighbors from the Albemarle, who had come to the celebration of New Bern's founding, continued to carouse around the big bonfire with the Palatines. Each outburst of rage and frustration from Taylor's house brought a roar of raucous laughter from the wild gang around the fire.

Loudly some wag in the crowd pointed out to Michel that his English was not nearly so fine as that of King Taylor! Another pointed out that the beating Michel gave him only served to sharpen Taylor's tongue! At this, Michel jumped up, kicked a shower of burning embers from the fire, and vowed to kick as many sparks from the Indian leader's arsch!

Michel ran to Taylor's house, followed by the drunken mob that roared its approval, and kicked open the door. King Taylor was astonished to find his privacy so violated. As he rose to protest, the enraged German pounced on him. Michel again pummeled Taylor mercilessly, knocking him down. When the Indian chief struggled to rise, Michel slammed a boot to his body that kicked him out the door. That was the way King Taylor left his home in Cartuca.

The Indian leader sprawled unconscious in the dirt, as Michel ordered the other Indians from their home. The women of the Taylor household were allowed to hastily gather a few belongings, as the young Indian men picked up their battered father and erstwhile spokesman, of whom they had always been so proud. Then they vanished into the darkness, the way Indians always do.

This was really the opening battle of the Tuscarora War, of which John Lawson was the first officially documented victim. This was the opening battle of the war that pitted the Iroquoian Tuscaroras of Roquis Pocosin, who allied themselves with their English neighbors, against a hodge-podge of Sioux, Algonquins and renegade Iroquois (mostly Tuscaroras)--who saw their destinies prefigured in the disgraceful beating Taylor took. King Taylor--who had so prided himself on his English ancestry.....

Full Article Here:

http://www.dickshovel.com/coreewho.html

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

11/05/2007 04:23:00 PM

![]()

Labels: colonies, crotoans, drake, England, indians, john lawson, Lumbee, manteo, Philip Amadas

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

If you lost this cannon, please call scientists

A find at sea from 24 years ago begs the question of about how it came to rest on the ocean floor.

Courtesy of Roanoke Island Festival Park, September 19, 2007

This cannon on display at Roanoke Island Festival Park in North Carolina

was found off the Virginia coast in 1983 by scallop fishermen.

Researchers dated it to the 1580s.

BY PATRICK LYNCH 247-4534

September 23, 2007

A small cannon dredged up by scallop fishermen off the Virginia coast 24 years ago is getting a second look as a possible mark of a shipwreck with a - potentially - very interesting history.Some historians believe it is an English cannon from the 1580s, and if the dating is correct it would be one of the oldest English artifacts ever found in the Americas.Its mere existence begs larger questions: How did it get to the bottom of the ocean? Did it merely go overboard or did a shipwreck leave it there? Whose ship was it? When did it happen?

Full Article Here:http://www.dailypress.com/news/dp-21163sy0sep23,0,4284916,full.story

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

9/25/2007 06:59:00 PM

![]()

Labels: 16th century, artifact, cannon, colonies, drake, England, john white, lost colony, roanoke, walter raleigh