Anne Poole (left), Research Director for the Lost Colony Research Group, and Roberta Estes (right) sifting through the dirt for artifacts. Roberta Estes

Anne Poole (left), Research Director for the Lost Colony Research Group, and Roberta Estes (right) sifting through the dirt for artifacts. Roberta Estes

The legend of the Lost Colony of Roanoke has haunted American history for centuries. In July 1587, a British colonist named John White accompanied 117 people to settle a small island sheltered within the barrier islands of what would become North Carolina’s Outer Banks. When conditions proved harsher than anticipated, White agreed to sail back to Britain to shore up the settlement’s supplies—a trip that should have lasted a few months.

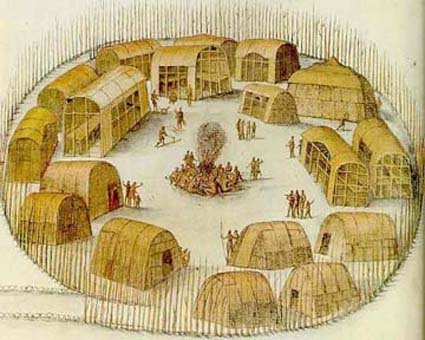

When White belatedly returned in 1590, the colonists had vanished—more than 100 men, women, and young children, their shelters and belongings, all gone. According to White’s writings, the only trace they left behind was a structure of tree trunks, with a single word carved into one post: CROATOAN.

The creepiness of the Lost Colonists’ disappearance didn’t discourage future American settlement. Nor has the lack of clues about their fate discouraged professional and amateur historians from trying to figure out what happened to them.

Archaeological digs, weather records, historical writings, genealogy—none have fully answered the question of what happened during White’s absence. But Roberta Estes, who owns DNAeXplain, a company that interprets the results of genetic heritage tests, is looking to DNA for help. Her hypothesis is that the Lost Colonists survived, and that evidence of their salvation is tucked away in the mitochondrial or Y chromosomal DNA of living descendents.

“They were stranded,” Estes says of the settlers. “They knew they couldn’t survive there on the island.” The colonists’ solution, in her estimation, was to go native.

“Croatoan,” Estes explains, was a message to White indicating that the colonists had gone to live with the Croatan Indians who lived on nearby Hatteras Island. Estes’s volunteer organization, the Lost Colony Research Group, is recruiting people from the area to submit DNA samples and family histories to test her theory.

Studying patterns of short tandem repeats (STRs) on the Y chromosomes of living men can determine whether they are likely to share a common ancestor that was a member of the Lost Colony. For example, Estes can compare the STR profile of a man whose family history suggests that his ancestors lived on Hatteras Island in the 17th century against genetic databases to see if he’s related to anyone with a Lost Colonist surname, such as Dare, Hewet, or Rufoote.

Additionally, it’s possible to scan that man’s mitochondrial or Y chromosomal DNA for evidence of Native American heritage, creating a clearer picture of what became of the vanished colonists. “It is true that with Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA you can assign them unequivocally to different ethnic groups,” says Ugo Perego, a senior researcher at the Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation. But, he adds, it would be difficult to tell exactly when the European ancestry was introduced.

Estes has amassed early land-grant records detailing who lived in the Outer Banks area a few centuries ago. Some of the putative Native Americans living there are thought to have adopted the last names of their European neighbors, she says. If Estes can show that the descendents of these Native American families have DNA matching families with Lost Colony surnames, that would suggest that the colonists mixed with the Croatan Indians.

Cont. here:

http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/31423/title/Lost-Colony-DNA-/

This blog is © History Chasers

Click here to view all recent Lost Colony Research Group Blog posts

Anne Poole (left), Research Director for the Lost Colony Research Group, and Roberta Estes (right) sifting through the dirt for artifacts. Roberta Estes