by Janet Crain

This is the second part of a series about the conditions which lead up to Bacon's Rebellion, felt by some to have precipitated the American Revolution by one hundred years.

================================================

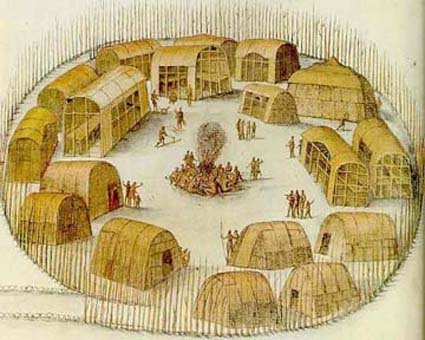

It was a complex chain of oppression in Virginia. The Indians were plundered by white frontiersmen, who were taxed and controlled by the Jamestown elite. And the whole colony was being exploited by England, which bought the colonists' tobacco at prices it dictated and made 100,000 pounds a year for the King. Berkeley himself, returning to England years earlier to protest the English Navigation Acts, which gave English merchants a monopoly of the colonial trade, had said:

... we cannot but resent, that forty thousand people should be impoverish'd to enrich little more than forty Merchants, who being the only buyers of our Tobacco, give us what they please for it, and after it is here, sell it how they please; and indeed have forty thousand servants in us at cheaper rates, than any other men have slaves....

From the testimony of the governor himself, the rebellion against him had the overwhelming support of the Virginia population. A member of his Council reported that the defection was "almost general" and laid it to "the Lewd dispositions of some Persons of desperate Fortunes" who had "the Vaine hopes of takeing the Countrey wholley out of his Majesty's handes into their owne." Another member of the Governor's Council, Richard Lee, noted that Bacon's Rebellion had started over Indian policy. But the "zealous inclination of the multitude" to support Bacon was due, he said, to "hopes of levelling."

"Levelling" meant equalizing the wealth. Levelling was to be behind countless actions of poor whites against the rich in all the English colonies, in the century and a half before the Revolution.

The servants who joined Bacon's Rebellion were part of a large underclass of miserably poor whites who came to the North American colonies from European cities whose governments were anxious to be rid of them. In England, the development of commerce and capitalism in the 1500s and 1600s, the enclosing of land for the production of wool, filled the cities with vagrant poor, and from the reign of Elizabeth on, laws were passed to punish them, imprison them in workhouses, or exile them. The Elizabethan definition of "rogues and vagabonds" included:

... All persons calling themselves Schollers going about begging, all Seafaring men pretending losses of their Shippes or goods on the sea going about the Country begging, all idle persons going about in any Country either begging or using any subtile crafte or unlawful Games ... comon Players of Interludes and Minstrells wandring abroade ... all wandering persons and comon Labourers being persons able in bodye using loytering and refusing to worke for such reasonable wages as is taxed or commonly given....

Such persons found begging could be stripped to the waist and whipped bloody, could be sent out of the city, sent to workhouses, or transported out of the country.

In the 1600s and 1700s, by forced exile, by lures, promises, and lies, by kidnapping, by their urgent need to escape the living conditions of the home country, poor people wanting to go to America became commodities of profit for merchants, traders, ship captains, and eventually their masters in America. Abbot Smith, in his study of indentured servitude,

Colonists in Bondage, writes: "From the complex pattern of forces producing emigration to the American colonies one stands out clearly as most powerful in causing the movement of servants. This was the pecuniary profit to be made by shipping them."

After signing the indenture, in which the immigrants agreed to pay their cost of passage by working for a master for five or seven years, they were often imprisoned until the ship sailed, to make sure they did not run away. In the year 1619, the Virginia House of Burgesses, born that year as the first representative assembly in America (it was also the year of the first importation of black slaves), provided for the recording and enforcing of contracts between servants and masters. As in any contract between unequal powers, the parties appeared on paper as equals, but enforcement was far easier for master than for servant.

The voyage to America lasted eight, ten, or twelve weeks, and the servants were packed into ships with the same fanatic concern for profits that marked the slave ships. If the weather was bad, and the trip took too long, they ran out of food. The sloop

Sea-Flower, leaving Belfast in 1741, was at sea sixteen weeks, and when it arrived in Boston, forty-six of its 106 passengers were dead of starvation, six of them eaten by the survivors. On another trip, thirty-two children died of hunger and disease and were thrown into the ocean. Gottlieb Mittelberger, a musician, traveling from Germany to America around 1750, wrote about his voyage:

During the journey the ship is full of pitiful signs of distress-smells, fumes, horrors, vomiting, various kinds of sea sickness, fever, dysentery, headaches, heat, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth-rot, and similar afflictions, all of them caused by the age and the high salted state of the food, especially of the meat, as well as by the very bad and filthy water.. .. Add to all that shortage of food, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, fear, misery, vexation, and lamentation as well as other troubles.... On board our ship, on a day on which we had a great storm, a woman ahout to give birth and unable to deliver under the circumstances, was pushed through one of the portholes into the sea....

Indentured servants were bought and sold like slaves. An announcement in the

Virginia Gazette, March 28, 1771, read:

Just arrived at Leedstown, the Ship Justitia, with about one Hundred Healthy Servants, Men Women & Boys... . The Sale will commence on Tuesday the 2nd of April.

Against the rosy accounts of better living standards in the Americas one must place many others, like one immigrant's letter from America: "Whoever is well off in Europe better remain there. Here is misery and distress, same as everywhere, and for certain persons and conditions incomparably more than in Europe."

Beatings and whippings were common. Servant women were raped. One observer testified: "I have seen an Overseer beat a Servant with a cane about the head till the blood has followed, for a fault that is not worth the speaking of...." The Maryland court records showed many servant suicides. In 1671, Governor Berkeley of Virginia reported that in previous years four of five servants died of disease after their arrival. Many were poor children, gathered up by the hundreds on the streets of English cities and sent to Virginia to work.

The master tried to control completely the sexual lives of the servants. It was in his economic interest to keep women servants from marrying or from having sexual relations, because childbearing would interfere with work. Benjamin Franklin, writing as "Poor Richard" in 1736, gave advice to his readers: "Let thy maidservant be faithful, strong and homely."

Servants could not marry without permission, could be separated from their families, could be whipped for various offenses. Pennsylvania law in the seventeenth century said that marriage of servants "without the consent of the Masters .. . shall be proceeded against as for Adultery, or fornication, and Children to be reputed as Bastards."

Although colonial laws existed to stop excesses against servants, they were not very well enforced, we learn from Richard Morris's comprehensive study of early court records in

Government and Labor in Early America. Servants did not participate in juries. Masters did. (And being propertyless, servants did not vote.) In 1666, a New England court accused a couple of the death of a servant after the mistress had cut off the servant's toes. The jury voted acquittal. In Virginia in the 1660s, a master was convicted of raping two women servants. He also was known to beat his own wife and children; he had whipped and chained another servant until he died. The master was berated by the court, but specifically cleared on the rape charge, despite overwhelming evidence.

Sometimes servants organized rebellions, but one did not find on the mainland the kind of large- scale conspiracies of servants that existed, for instance, on Barbados in the West Indies. (Abbot Smith suggests this was because there was more chance of success on a small island.)

However, in York County, Virginia, in 1661, a servant named Isaac Friend proposed to another, after much dissatisfaction with the food, that they "get a matter of Forty of them together, and get Gunnes & hee would be the first & lead them and cry as they went along, 'who would be for Liberty, and free from bondage', & that there would enough come to them and they would goe through the Countrey and kill those that made any opposition and that they would either be free or dye for it." The scheme was never carried out, but two years later, in Gloucester County, servants again planned a general uprising. One of them gave the plot away, and four were executed. The informer was given his freedom and 5,000 pounds of tobacco. Despite the rarity of servants' rebellions, the threat was always there, and masters were fearful.

Finding their situation intolerable, and rebellion impractical in an increasingly organized society, servants reacted in individual ways. The files of the county courts in New England show that one servant struck at his master with a pitchfork. An apprentice servant was accused of "laying violent hands upon his ... master, and throwing him downe twice and feching bloud of him, threatening to breake his necke, running at his face with a chayre...." One maidservant was brought into court for being "bad, unruly, sulen, careles, destructive, and disobedient."

After the participation of servants in

Bacon's Rebellion, the Virginia legislature passed laws to punish servants who rebelled. The preamble to the act said:

Whereas many evil disposed servants in these late tymes of horrid rebellion taking advantage of the loosnes and liberty of the tyme, did depart from their service, and followed the rebells in rebellion, wholy neglecting their masters imploymcnt whereby the said masters have suffered great damage and injury....

Two companies of English soldiers remained in Virginia to guard against future trouble, and their presence was defended in a report to the Lords of Trade and Plantation saying: "Virginia is at present poor and more populous than ever. There is great apprehension of a rising among the servants, owing to their great necessities and want of clothes; they may plunder the storehouses and ships."

Escape was easier than rebellion.

"Numerous instances of mass desertions by white servants took place in the Southern colonies," reports Richard Morris, on the basis of an inspection of colonial newspapers in the 1700s.

"The atmosphere of seventeenth-century Virginia," he says,

"was charged with plots and rumors of combinations of servants to run away." The Maryland court records show, in the 1650s, a conspiracy of a dozen servants to seize a boat and to resist with arms if intercepted. They were captured and whipped.

The mechanism of control was formidable. Strangers had to show passports or certificates to prove they were free men. Agreements among the colonies provided for the extradition of fugitive servants- these became the basis of the clause in the U.S. Constitution that persons

"held to Service or Labor in one State ... escaping into another ... shall be delivered up...." Sometimes, servants went on strike. One Maryland master complained to the Provincial Court in 1663 that his servants did "peremptorily and positively refuse to goe and doe their ordinary labor." The servants responded that they were fed only "Beanes and Bread" and they were "soe weake, wee are not able to perform the imploym'ts hee puts us uppon." They were given thirty lashes by the court.

More than half the colonists who came to the North American shores in the colonial period came as servants. They were mostly English in the seventeenth century, Irish and German in the eighteenth century. More and more, slaves replaced them, as they ran away to freedom or finished their time, but as late as 1755, white servants made up 10 percent of the population of Maryland.

What happened to these servants after they became free? There are cheerful accounts in which they rise to prosperity, becoming landowners and important figures. But Abbot Smith, after a careful study, concludes that colonial society "was not democratic and certainly not equalitarian; it was dominated by men who had money enough to make others work for them." And: "Few of these men were descended from indentured servants, and practically none had themselves been of that class."

After we make our way through Abbot Smith's disdain for the servants, as "men and women who were dirty and lazy, rough, ignorant, lewd, and often criminal," who "thieved and wandered, had bastard children, and corrupted society with loathsome diseases," we find that "about one in ten was a sound and solid individual, who would if fortunate survive his 'seasoning,' work out his time, take up land, and wax decently prosperous." Perhaps another one in ten would become an artisan or an overseer. The rest, 80 percent, who were "certainly ... shiftless, hopeless, ruined individuals," either "died during their servitude, returned to England after it was over, or became 'poor whites.'"

http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/zinnvil3.html