Copyright 2007, Roberta Estes, all rights reserved

http://www.dnaexplain.com/

Many American families carry oral histories of Native American heritage. Most often, we think of either the Western tribes who still reside in or near their indigenous homes, or the Cherokee who were displaced in the 1830s, forced to march from Appalachia to Oklahoma in the dead of winter, an event subsequently known as the Trail of Tears.

In truth, the history of Native American heritage in North America is much, much more complex. It is probable that many of the people who carry oral history of “Cherokee heritage” are actually descended from a tribe other than the Cherokee initially. The Cherokee were well known for accepting remnants of other tribes whose members and numbers had been decimated by disease or war. Sometimes these alliances were created for mutual protection.

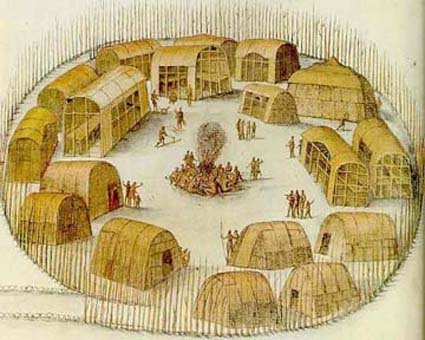

The Cherokees were not the only tribe in the Eastern United States. The Eastern seaboard was widely populated by varying tribes, some related and affiliated, and some not. There were in fact three major language groupings, Algonquin, Souian and Iroquoian scattered throughout the Eastern seaboard northward into Canada, westward to Appalachia and south to the Gulf of Mexico.

People from Africa were also imported very early, often, but not always, as slaves. Jamestown shows evidence of individuals of African heritage. Those who were later brought specifically as slaves sometimes ran away, escaping into the Native population. Conversely, Indians were often taken or sold by defeating tribes into slavery as well.

In the early years of settlement, European women were scarce. Some men immigrated with wives and families, but most did not, and few women came alone. Therefore, with nature taking its course, it is not unreasonable to surmise that many of the early settlers traded with, worked alongside and married into indigenous families, especially immigrants who were not wealthy. Wealthy individuals traveled back and forth across the Atlantic and could bring a bride on a subsequent journey.

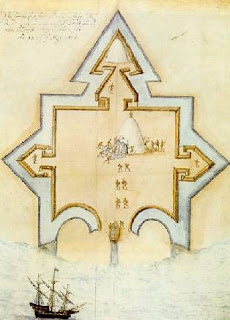

Further complicating matters, there were numerous “lost” individuals of varying ethnicity in the very early years of colonization. Specifically, Juan Pardo established forts in many southern states from Florida to Mexico beginning in 1566. The Spanish settled Florida and explored the interior beginning in 1521, settling Santa Elena Island in present day South Carolina from 1566-1576. Their forays extended as far North as present day East Tennessee. In 1569, 3 English men arrived in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia having set out on foot with 100 men 4000 miles earlier in Tampico, Mexico. These individuals are in addition to the well-known Lost Colony of Roanoke, and the less well-known earlier military expeditions on which several individuals were “lost” or left behind.

What does this mean to the family historian who is trying to prove their genealogy and understand better just who they are and where they come from?

If your family has a long-standing oral history of Native American heritage, it is probably true. Historically, Native people were classified as “non-white” which severely limited (and sometimes prevented) their ability to function as free, white, people with equal rights. This means that free “people of color” often could not vote, could not own land, and could not attend schools along with white people, if at all.

Furthermore, laws varied and how much non-white heritage constituting “people of color” ranged from the infamous “one drop” rule to lesser admixture, sometimes much more liberal, to only the third generation. In essence, as soon as individuals could become or pass for “white” they did. It was socially and financially advantageous. It is not unusual to find a family who moved from one location to another, often westward, and while they were classified as mulatto in their old home, they were white in their new location.

Often there were only three or sometimes four classifications available, white, negro or black, mulatto and Indian. Sometimes Indian was a good thing to be, because in some colonial states, Indians weren’t taxed. However, this also means their existence in a particular area often went unrecorded.

Any classification other than white meant in terms of social and legal status that these people were lesser citizens. Therefore, Native American or other heritage that was not visually obvious was hidden and whispered about, sometimes renamed to much less emotionally and socially charged monikers, such as Black Dutch, Black Irish and possibly also Portuguese.

For genalogists who are lucky, there are records confirming their genealogy, such as the Dawes Rolls and other legal documents. More often, there are only hints, if even that, such as a census where an ancestor is listed as mulatto, or some other document that hints at their heritage. Most often though, the stories are very vague, and were whispered or hidden for generations. References may be oral or found in old letters or documents. Supporting documentation is often missing.

Many times, it was the woman of the couple who was admixed initially, of course leading to admixed children, but with 50% less admixture than their mixed parent. It was much more common for a male of European stock to intermarry with Native or admixed women, rather than the other way around.

This means to genetic genealogists today, that they are likely to meet with frustration when attempting to document Native heritage in a male line.

Let’s take a look at why this is and how we can build a DNA pedigree chart to track our ancestry.

Continue here:http://www.genpage.com/Native_American_Heritage.html#Continued