By Janet Crain

Many people do not know what it really meant to be an indentured servant when this country was a British colony. They imagine an agreement was made between two adults that in return for the cost of transportation here, the indentured servant would work a period of time, usually 7 years, in return for his or her debt. At first a small acreage was even awarded along with a sum of money and suit of clothes. That was soon phased out. There were many opportunities for the exploitation of this system and most were employed. It became common for people including children to be kidnapped (kid nabbed). The courts sent many persons convicted of crimes large and small to the colonies. Poor children were sent so that they not be a burden on the government. Young women and men were tricked aboard or knocked in the head and carried on board. It made no difference once the ship set sail. They were cut off forever from their friends and families.

Conditions on board were terrible. The ship's captains transported as many as possible, as cheaply as possible, and sold their indentureships once in the colonies. No attempt was made to keep families together. Conditions in the new country were so horrible that as many as 4 out of 5 soon died.

Eventually conditions became so bad that some of these people banded together and rebelled. It was called "Bacon's Rebellion".

Some call this the first stirrings of the eventual American Revolution.

Persons of Mean and Vile Condition

In 1676, seventy years after Virginia was founded, a hundred years before it supplied leadership for the American Revolution, that colony faced a rebellion of white frontiersmen, joined by slaves and servants, a rebellion so threatening that the governor had to flee the burning capital of Jamestown, and England decided to send a thousand soldiers across the Atlantic, hoping to maintain order among forty thousand colonists. This was Bacon's Rebellion. After the uprising was suppressed, its leader, Nathaniel Bacon, dead, and his associates hanged, Bacon was described in a Royal Commission report: He was said to be about four or five and thirty years of age, indifferent tall but slender, black-hair'd and of an ominous, pensive, melancholly Aspect, of a pestilent and prevalent Logical discourse tending to atheisme... . He seduced the Vulgar and most ignorant people to believe (two thirds of each county being of that Sort) Soc that their whole hearts and hopes were set now upon Bacon. Next he charges the Governour as negligent and wicked, treacherous and incapable, the Lawes and Taxes as unjust and oppressive and cryes up absolute necessity of redress. Thus Bacon encouraged the Tumult and as the unquiet crowd follow and adhere to him, he listeth them as they come in upon a large paper, writing their name circular wise, that their Ringleaders might not be found out. Having connur'd them into this circle, given them Brandy to wind up the charme, and enjoyned them by an oath to stick fast together and to him and the oath being administered, he went and infected New Kent County ripe for Rebellion.

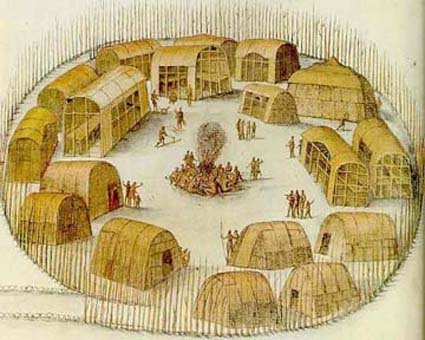

Bacon's Rebellion began with conflict over how to deal with the Indians, who were close by, on the western frontier, constantly threatening. Whites who had been ignored when huge land grants around Jamestown were given away had gone west to find land, and there they encountered Indians. Were those frontier Virginians resentful that the politicos and landed aristocrats who controlled the colony's government in Jamestown first pushed them westward into Indian territory, and then seemed indecisive in fighting the Indians? That might explain the character of their rebellion, not easily classifiable as either antiaristocrat or anti-Indian, because it was both.

And the governor, William Berkeley, and his Jamestown crowd-were they more conciliatory to the Indians (they wooed certain of them as spies and allies) now that they had monopolized the land in the East, could use frontier whites as a buffer, and needed peace? The desperation of the government in suppressing the rebellion seemed to have a double motive: developing an Indian policy which would divide Indians in order to control them (in New England at this very time, Massasoit's son Metacom was threatening to unite Indian tribes, and had done frightening damage to Puritan settlements in "King Philip's War"); and teaching the poor whites of Virginia that rebellion did not pay-by a show of superior force, by calling for troops from England itself, by mass hanging.

Violence had escalated on the frontier before the rebellion. Some Doeg Indians took a few hogs to redress a debt, and whites, retrieving the hogs, murdered two Indians. The Doegs then sent out a war party to kill a white herdsman, after which a white militia company killed twenty-four Indians. This led to a series of Indian raids, with the Indians, outnumbered, turning to guerrilla warfare. The House of Burgesses in Jamestown declared war on the Indians, but proposed to exempt those Indians who cooperated. This seemed to anger the frontiers people, who wanted total war but also resented the high taxes assessed to pay for the war.

Times were hard in 1676. "There was genuine distress, genuine poverty.... All contemporary sources speak of the great mass of people as living in severe economic straits," writes Wilcomb Washburn, who, using British colonial records, has done an exhaustive study of Bacon's Rebellion. It was a dry summer, ruining the corn crop, which was needed for food, and the tobacco crop, needed for export. Governor Berkeley, in his seventies, tired of holding office, wrote wearily about his situation: "How miserable that man is that Governes a People where six parts of seaven at least are Poore Endebted Discontented and Armed."

His phrase "six parts of seaven" suggests the existence of an upper class not so impoverished. In fact, there was such a class already developed in Virginia. Bacon himself came from this class, had a good bit of land, and was probably more enthusiastic about killing Indians than about redressing the grievances of the poor. But he became a symbol of mass resentment against the Virginia establishment, and was elected in the spring of 1676 to the House of Burgesses. When he insisted on organizing armed detachments to fight the Indians, outside official control, Berkeley proclaimed him a rebel and had him captured, whereupon two thousand Virginians marched into Jamestown to support him. Berkeley let Bacon go, in return for an apology, but Bacon went off, gathered his militia, and began raiding the Indians.

Bacon's "Declaration of the People" of July 1676 shows a mixture of populist resentment against the rich and frontier hatred of the Indians. It indicted the Berkeley administration for unjust taxes, for putting favorites in high positions, for monopolizing the beaver trade, and for not protecting the western formers from the Indians. Then Bacon went out to attack the friendly Pamunkey Indians, killing eight, taking others prisoner, plundering their possessions.

There is evidence that the rank and file of both Bacon's rebel army and Berkeley's official army were not as enthusiastic as their leaders. There were mass desertions on both sides, according to Washburn. In the fall, Bacon, aged twenty-nine, fell sick and died, because of, as a contemporary put it, "swarmes of Vermyn that bred in his body." A minister, apparently not a sympathizer, wrote this epitaph: Bacon is Dead I am sorry at my heart,

The rebellion didn't last long after that. A ship armed with thirty guns, cruising the York River, became the base for securing order, and its captain, Thomas Grantham, used force and deception to disarm the last rebel forces. Coming upon the chief garrison of the rebellion, he found four hundred armed Englishmen and Negroes, a mixture of free men, servants, and slaves. He promised to pardon everyone, to give freedom to slaves and servants, whereupon they surrendered their arms and dispersed, except for eighty Negroes and twenty English who insisted on keeping their arms. Grantham promised to take them to a garrison down the river, but when they got into the boat, he trained his big guns on them, disarmed them, and eventually delivered the slaves and servants to their masters. The remaining garrisons were overcome one by one. Twenty-three rebel leaders were hanged.

That lice and flux should take the hangmans part.

To be Cont.

http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/zinnvil3.html

© History Chasers

Click here to view all recent Searching for the Lost Colony DNA Blog posts

Sunday, February 1, 2009

Persons of Mean and Vile Condition pt. 1

by Howard Zinn

Posted by

Historical Melungeons

at

2/01/2009 11:43:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Barbados, England, indentured servants, Ireland, kidnapped