by Janet Crain

There was some misunderstanding when this paper first appeared that the author was saying some of the groups studied such as the Melungeons had no Indian ancestry. That was not the intent. If the entire JoGG paper is read it will become clear that this is a very serious, perhaps the first in some aspects, effort to explain why we are not seeing the Native American genetic testing results we would expect.

Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Genealogy and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony of Roanoke.

Roberta Estes

Abstract

Within genealogy circles, family stories of Native American1 heritage exist in many families whose American ancestry is rooted in Colonial America and traverses Appalachia. The task of finding these ancestors either genealogically or using genetic genealogy is challenging.

With the advent of DNA testing, surname and other special interest projects2, tools now exist to facilitate grouping participants in a way that allows one to view populations in historical fashions. This paper references and uses data from several of these public projects, but particularly the Melungeon, Lumbee, Waccamaw, North Carolina Roots and Lost Colony projects3.

The Lumbee have long claimed descent from the Lost Colony via their oral history4. The Lumbee DNA Project shows significantly less Native American ancestry than would be expected with 96% European or African Y chromosomal DNA. The Melungeons, long held to be mixed European, African and Native show only one ancestral family with Native DNA5. Clearly more testing would be advantageous in all of these projects.

This phenomenon is not limited to these groups, and has been reported by other researchers such as Bolnick (et al, 2006) where she reports finding in 16 Native American populations with northeast or southeast roots that 47% of the families who believe themselves to be full blooded or no less than 75% Native with no paternal European admixture find themselves carrying European or African y-line DNA. Malhi (et al, 2008) reported that in 26 Native American populations non-Native American Y chromosomal DNA frequency as high as 88% is found in the Canadian northeast, southwest of Hudson Bay. Malhi’s conclusions suggest that perhaps there was early1 introduction of European DNA in that population.

The significantly higher non-Native DNA frequency found among present day Lumbee descendants may be due in part to the unique history of the Eastern seaboard Indian tribes of that area or to the admixture of European DNA by the assimilation of the Lost Colony of Roanoke after 1587, or both.

European contact may have begun significantly before the traditionally held dates of 1492 with Columbus’ discovery of America or 1587 with the Lost Colony of Roanoke which is generally and inaccurately viewed as the first European settlement attempt. Several documented earlier contacts exist and others were speculated, but the degree of contact and infusion of DNA into the Native population is unknown.

Wave after wave of disease introduced by European and African contact and warfare decimated the entire tribal population. Warfare took comparatively more male than female lives, encouraging the adoption of non-Indian males into the tribes as members or guests. An extensive English trader network combined with traditional Native American social practices that encouraged sexual activity with visitors was another avenue for European DNA to become infused into Eastern seaboard tribes.

1 Native, Native American, American Indian and Indian are used interchangeably to indicate the original inhabitants of North American before the European colonists arrived.

2 Available through Family Tree DNA, www.familytreedna.com

3 See Acknowledgement section for web addresses of the various projects. Note that participants join these projects voluntarily and are not recruited for specific traits as in other types of scientific studies. Some projects, such as the Lost Colony projects, screen applicants for appropriateness prior to joining. For the join criteria, please see the FAQ at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~molcgdrg/faqs/faq3.htm.

4 The oral history exists tribe-wide, but specifically involves Virginia Dare and the colonists Henry and Richard Berry. Genealogies are relatively specific about the line of descent.

5 The Melungeon DNA project, while initially included in this research, was subsequently removed from the report because of the lack of Native American ancestry and no direct connection to the Lost Colonists. The Lumbee may be connected to the Melungeons, but that remains unproven.

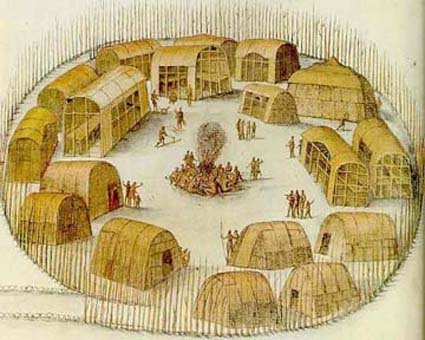

Eastern Seaboard Native Americans

The genealogies of many families contain oral histories of Native ancestors. With the advent of genealogical DNA testing, confirmation of those long-held and cherished family stories about Native American ancestors can now be confirmed or denied, assuming one can find the right cousin and persuade them to test. Many surprises await DNA participants, and not always positive surprises if the search is for Native American ancestors. Those who are supposed to be, aren’t, and occasionally a surprise Native American ancestor appears via the announcement of their haplogroup.

What DNA testing offers to the genealogist, it also offers to the historian. With the advent of projects other than surname projects, meaning both geographically based projects and haplogroup projects, historians are offered a new way to look at and compare data.

Excellent examples of this type of project are the Lumbee, East Carolina Roots, Melungeon and Waccamaw projects.

A similar project of significantly wider scope is the 1587 Lost Colony of Roanoke DNA project. When the author founded the project in early 2007, it was thought that the answer would be discovered relatively quickly and painlessly, meaning that significant cooperation and genealogical research from local families would occur and that the surnames and families in England would be relatively easy to track. Nothing could be further from the truth. The paucity of early records in the VA/NC border region combined with English records that are difficult to search, especially from a distance, are located in many various locations and are often written in Latin has proven to be very challenging. The Lost Colony project has transformed itself into a quest to solve a nearly 425 year old mystery, the oldest “cold case” in America. However, this is not the first attempt. Historical icons David Beers Quinn (1909-2002) and William S. Powell devoted their careers to the unending search for the colonists, both here in the US in terms of their survival and in Great Britain in terms of their original identities. However, neither of those men had the benefit of DNA as a tool and we are building upon their work, and others.

One cannot study the Lost Colonists, referred to here as colonists, without studying the history of the eastern North Carolina area in general including early records, the British records and critically, the history of the Native people of the Outer Banks area of North Carolina. A broad research area in the early years (pre-1700 to as late as 1750), would be defined as coastal North Carolina and Virginia and into South Carolina in the later years (1712 to about 1800). Initially both Carolinas were in fact Virginia, North Carolina being formed in 1663 as Carolina. When South Carolina split off in 1712, the States of both North and South Carolina were created from the original Carolina.

Copyright 2009, all rights reserved, accepted for publication at JoGG

Roberta@dnaexplain.com or robertajestes@att.net

Figure 5: http://www.nationmaster.com/encyclopedia/Image:Algonquian-langs.png

Read the entire paper here:

http://www.jogg.info/52/index.html

There are 4 supplementary files with a lot of good data in there as well.This blog is © History Chasers

Click here to view all recent Searching for the Lost Colony DNA Blog posts