By Charles C. Mann

It is just possible that John Rolfe was responsible for the worms—specifically the common night crawler and the red marsh worm, creatures that did not exist in the Americas before Columbus. Rolfe was a colonist in Jamestown, Virginia, the first successful English colony in North America. Most people know him today, if they know him at all, as the man who married Pocahontas. A few history buffs understand that Rolfe was one of the primary forces behind Jamestown's eventual success. The worms hint at a third, still more important role: Rolfe inadvertently helped unleash a convulsive and permanent change in the American landscape.

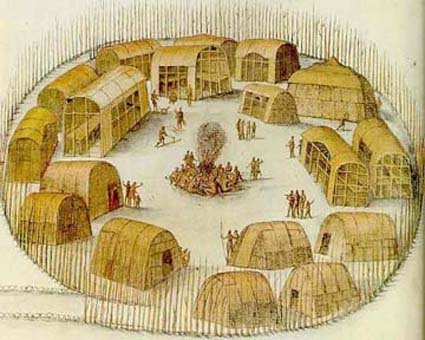

Like many young English blades, Rolfe smoked—or, as the phrase went in those days, "drank"—tobacco, a fad since the Spanish had first carried back samples ofNicotiana tabacum from the Caribbean. Indians in Virginia also drank tobacco, but it was a different species, Nicotiana rustica. Virginia leaf was awful stuff, wrote colonist William Strachey: "poor and weak and of a biting taste." After arriving in Jamestown in 1610, Rolfe talked a shipmaster into bringing him N. tabacum seeds from Trinidad and Venezuela. Six years later Rolfe returned to England with his wife, Pocahontas, and the first major shipment of his tobacco. "Pleasant, sweet, and strong," as Rolfe's friend Ralph Hamor described it, Jamestown's tobacco was a hit. By 1620 the colony exported up to 50,000 pounds (23,000 kilograms) of it—and at least six times more a decade later. Ships bellied up to Jamestown and loaded up with barrels of tobacco leaves. To balance the weight, sailors dumped out ballast, mostly stones and soil. That dirt almost certainly contained English earthworms.

And little worms can trigger big changes. The hardwood forests of New England and the upper Midwest, for instance, have no native earthworms—they were apparently wiped out in the last Ice Age. In such worm-free woodlands, leaf litter piles up in drifts on the forest floor. But when earthworms are introduced, they can do away with the litter in a few months. The problem is that northern trees and shrubs beneath the forest canopy depend on that litter for food. Without it, water leaches away nutrients formerly stored in the litter. The forest becomes more open and dry, losing much of its understory, including tree seedlings.