It’s a typical day at the Hatteras Histories and Mysteries Museum in Buxton, N.C., and Scott Dawson is buzzing around glass cases full of centuries-old arrowheads and broken pottery. Puzzled visitors listen as he explains for the gazillionth time the difference between fact and speculation. • He speaks with certainty in a voice tinged with more than a hint of frustration. • “Anybody who researches it knows that the colony came down here,” he says, confidently dismissing competing theories on America’s oldest unsolved mystery. • The artifacts, many unearthed during archaeological digs in the past year, may hold the clues that finally answer the question: What happened to the Lost Colony, a group of 117 Englishmen who settled on a tiny island off the North Carolina coast and then vanished with barely a trace?

“The two drops of Croatoan blood that I have have boiled over,” he said. “I want the history of this tribe and this island to stop being ignored.”

He’s counting on science to help him set the record straight.

It was 1587 when the group now known as the Lost Colony sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World on an adventure that ultimately fell far short of its intended purpose.

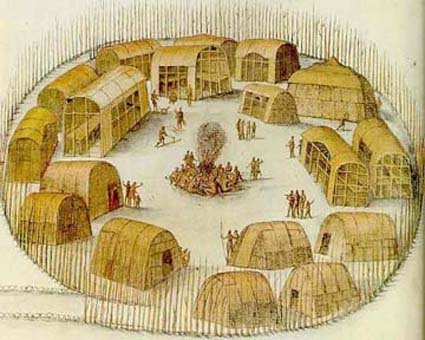

European explorers had been making the journey for years, and the first English contact with Native Americans on the Outer Banks is credited to a military expedition in 1584. Similar expeditions followed in 1585 and 1586.

The next year – 20 years before Jamestown was founded and 33 before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock – Sir Walter Raleigh dispatched the group of men, women and children in his bid to establish the first permanent English stronghold in America.

The colonists intended to settle near the Chesapeake Bay, but when their captain refused to sail farther north, they were forced to make a temporary home on Roanoke Island, where they’d planned to pick up 15 men left there the year before.

All they found were bones.

Less than a week after arriving, one colonist was killed, presumably by Indians.

In a desperate attempt to save the struggling colony, which included his newborn granddaughter Virginia Dare, Gov. John White and some colonists sailed back to England for help. White’s begging would go unheeded for three years.

With their leader gone and surrounded by strangers, the colonists lived out their final days. Nothing is known about what happened to them after White left.

Today, their legend lives on at the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island, where they were last seen by a white man. There, at Waterside Theater, an outdoor symphonic drama mixes fact with romantic speculation about the colony’s fate.

White returned in 1590, only to find the entire group gone. But they’d left behind one clue that continues to haunt modern-day historians and amateur sleuths: the word “Croatoan” carved into a tree.

Cont. here:

http://hamptonroads.com/2010/10/lost-colony-may-now-be-found

This blog is © History Chasers

Click here to view all recent Lost Colony Research Group Blog posts